Chronic Pancreatitis and

the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel

-

What It Is

What It Is - Symptoms

- Diagnosis

- Related Disorders

- Treatment

- What You Can Do

- Research News

- Related Links

- Veterinary Resources

The cavalier King Charles spaniel has a high prevalence of chronic pancreatitis and is believed to be predisposed to this disease, according to several recent reports. In a 2005 report by UK researchers, they found:

"There are strong breed-associations in CKCS and JRT, suggesting a possible genetic basis to the disease in these breeds."

This breed association has been confirmed in a 2007 UK report.*

* See also this 2007 UK report and this 2011 US report and this 2013 UK report.

Most cavaliers diagnosed with chronic pancreatitis are middle-aged or older. In a November 2014 presentation by Dr. Penny Watson, she stated that she has found the prevalence of chronic pancreatic disease in cavaliers to be as high as 80%.

What It Is

The pancreas is a gland which consists of about 98% exocrine acinar cells and 2% endocrine islets. The exocrine cells secrete enzymes* which aid the digestion of protein in the smaller intestine. The endocrine cells secrete insulin, which helps control carbohydrate metabolism, and glucagon, which offsets the action of the insulin.

* Enzymes secreted include lipase, alpha-amylase, phospholipase and the proteolytic enzymes elastase, chymotrypsin, and trypsin.

A normally functioning pancreas is protected from premature activation of

these caustic digestive enzymes, which could result in digesting the

pancreas itself. Pancreatitis occurs when the enzymes are activated

while still in the pancreas, thereby causing death to its tissue by

auto-digestion.

A normally functioning pancreas is protected from premature activation of

these caustic digestive enzymes, which could result in digesting the

pancreas itself. Pancreatitis occurs when the enzymes are activated

while still in the pancreas, thereby causing death to its tissue by

auto-digestion.

Pancreatitis is a common inflammatory disorder of the dog's pancreas, which can be either "acute" or "chronic". Acute pancreatitis is an inflammation which does not cause permanent damage to the pancreas and therefore is potentially reversible. Chronic pancreatitis, for which the cavalier appears predisposed and is at an increased risk, is a continuous inflammation which can cause permanent damage to the pancreas’ exocrine and endocrine tissues and result in insufficient creation and secretion of its enzymes, particularly an exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI).

The end stage of chronic pancreatitis may result in diabetes mellitus, due to extensive destruction of pancreatic tissues. In a January 2015 report, UK author Lucy J. Davison has observed that cases of diabetes mellitus often accompany exocrine pancreatic inflammation. She states:

"However, the question remains as to whether the diabetes mellitus causes the pancreatitis or whether, conversely, the pancreatitis leads to diabetes mellitus – as there is evidence to support both scenarios. The concurrence of diabetes mellitus and pancreatitis has clinical implications for case management as such cases may follow a more difficult clinical course, with their glycaemic control being 'brittle' as a result of variation in the degree of pancreatic inflammation. Problems may also arise if abdominal pain or vomiting lead to anorexia. In addition, diabetic cases with pancreatitis are at risk of developing exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in the following months to years, which can complicate their management further."

Contrary to earlier belief, no evidence has been found that high fat diets cause pancreatitis. However, because fat is harder to digest than other ingredients, researchers have found that high fat diets tend to increase the symptom of pain in dogs which already have chronic pancreatitis.

In this July 2013 article, a cavalier was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis, along with acute zinc toxicity following ingesting a metallic object which also resulted in hemolytic anemia.

RETURN TO TOP

Symptoms

The range of signs of chronic pancreatitis in cavaliers is from mild to severe. Classic signs include:

• abdominal pain

• vomiting

• diarrhea

• decrease/loss of appetite

• depression

• dehydration

• fever

• jaundice

• shortness of breath (dysspnea)

• weakness/lethargy

• shock

The pain can be severe and may cause the dog to take a “praying” position. The affected dog may also pass diarrhea or voluminous feces, with small amounts of fresh blood and/or mucous.

The clinical signs of pancreatitis may come and go, and they will vary with the severity of the disease. Low-grade cases may not show all of the classic symptoms and may be confused with inflammatory bowel disease or a chronic infection, such as a urinary tract infection. In severe cases, the dog may become dehydrated, may collapse, be in shock, and may even suffer renal shutdown and distressed breathing.

If a dog which has diabetes mellitus suddenly begins to lose weight unexpectedly, despite having a good appetite and being under diabetic control, the dog may have developed an exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) due to pancreatitis.

RETURN TO TOP

Diagnosis

Low grade chronic pancreatitis can be difficult to diagnose because their symptoms can be confused easily with other conditions. Recent studies have found a high rate of under-diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis in dogs. Initial diagnostic testing typically includes CBC blood panels, serum chemistry profile, urinalysis, and most recently, enzyme assays such as SNAP cPL.

-- enzyme assays

Enzyme assays -- catalytic, immuno, and enzymatic -- involve measuring levels of circulating pancreatic enzymes, including lipase, amylase, trypsin (cTLI), and canine pancreas specific lipase (cPLI). Measurement of elevated circulating enzymes, including amylase, lipase, cTLI, and cPLI currently are the best tests available for diagnoses. Nevertheless, no such assays have been found useful to assess for spontaneous pancreatitis.

Researchers are constantly seeking to improve the accuracy of diagnosing

pancreatitis. IDEXX Laboratories claims that its SPEC cPL test,

a quantitative immunoassay, is the most

accurate, even more so than ultrasounds. See the

IDEXX website for details.

However, the Spec cPL results reportedly take at least 24 hours to return,

which can be an important limitation for some patients.

Researchers are constantly seeking to improve the accuracy of diagnosing

pancreatitis. IDEXX Laboratories claims that its SPEC cPL test,

a quantitative immunoassay, is the most

accurate, even more so than ultrasounds. See the

IDEXX website for details.

However, the Spec cPL results reportedly take at least 24 hours to return,

which can be an important limitation for some patients.

IDEXX Labs also offers a SNAP cPL test (right), a semiquantitative cPL immunoassay, for diagnosing pancreatitis. See the IDEXX website for details. In a July 2012 report of a comparison of various cPLI tests on 84 dogs, the researchers found that:

"SNAP and SPEC have higher sensitivity for diagnosing clinical AP [acute pancreatitis] than does measurement of serum amylase or lipase activity. A positive SPEC or SNAP has a good positive predictive value (PPV) in populations likely to have AP and a good negative predictive value (NPV) when there is low prevalence of disease."

The study was sponsored by IDEXX, the producer of SNAP and SPEC tests.

The SNAP cPL test is considered to be a rapid point-of-care semiquantitative cPL immunoassay which permits a more rapid return of results. The SNAP cPL test can be used to rapidly rule out pancreatitis, and it is recommended that a positive result be followed by laboratory assessment using a quantitative immunoassay, such as the Spec cPL.

The VetScan cPL Rapid Test has been developed by Abaxis Laboratories, with the aim of combining the benefits of a quantitative assay with the point-of-care benefits of the SNAP cPL. The VetScan cPL is a semiquantitative immunoassay for the detection of cPL that gives rapid point-of-care results. Unlike the SNAP cPL, the results of this point-of-care assay are numerical rather than binary, and is able to distinguish between patients without pancreatitis, those with equivocal results, and those with cPL results consistent with pancreatitis.

Non-immunologic colorimetric lipase assays are also available. The Precision PSL Test by Antech Diagnostics is a non-immunologic colorimetric lipase assay which utilizes the substrate 1,2-o-dilauryl-rac-glycero-3-glutaric acid (6'-methyl-resorufin) ester (DGGR), which has been validated for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in dogs. See this March 2005 article. In this May 2015 abstract, the researchers found that the DGGR-based assay is not specific for pancreatic lipase. However, in this April 2018 article, the researchers found that "DGGR lipase is a reliable alternative to Spec cPL for the diagnosis of pancreatitis."

In a November 2015 article, a group of Japanese researchers examined the use of a new diagnostic laboratory test, Fuji Dri-Chem lipase (FDP lip), compared to amylase, in diagnosing acute pancreatitis (AP). They found that among 64 dogs, activities of amylase and FDC lip were significantly higher in the AP group than in the nonpancreatic disease (NP) group. They report that the sensitivity of FDP lip activity for diagnosing AP was 100%. They did not compare the FDC lip with IDEXX's SNAP cPL test. They concluded that "the measurement of FDC lip activity appears useful for diagnosing AP."

In a July 2015 study, Spanish researchers report finding that some dogs treated with anticonvulsants (phenobarbital and potassium bromide) may show an increase in canine pancreas-specific lipase, but its increase may not be associated with severe acute pancreatitis.

Other diagnostic tests are being studied, including peptides in the blood and urine, and levels of inflammatory mediators and cytokines in the blood.

RETURN TO TOP

-- ultrasound

Ultrasounds can be very specific for pancreatitis, depending upon the extent of inflammation, when performed by skilled operators. Therefore, pancreatic ultrasounds should be performed by ultrasound specialists. Low grade chronic pancreatitis is the most difficult to detect using ultrasound. The rate of accuracy of detecting the disorder by ultrasound is about 60% overall and higher by skilled operators using high quality equipment.

Ultrasound scans can detect pancreatic swelling, changes in echogenicity of the pancreas, fluid accumulation around the pancreas, and a mass effect in the area of the pancreas.

In a March 2022 article, UK veterinary researchers studied 66 dogs diagnosed with acute pancreatitis (AP), including 3 cavaliers (4.55%). They sought to determine by ultrasound any gastrointestinal (GI) wall changes in the dogs, especially whether the presence of neutrophilia, left shift, or toxic neutrophils would serve as markers of increased severity of inflammation.They found that 31 of the dogs (47%) had ultrasonographic gastrointestinal wall changes, most commonly in the duodenum. Of the dogs with gastrointestinal wall changes, 23 (74.2%) had wall thickening, 19 (61.3%) had abnormal wall layering, and 11 (35.5%) had wall corrugation. Only increased heart rates was an independent predictor of gastrointestinal wall changes, but because of possible other factors, they considered heart rate unlikely to be useful in indicating whether GI wall changes are likely to be present. They concluded that ultrasonographic gastrointestinal wall changes were relatively common in this population of dogs with AP and that the results may aid clinicians in interpreting ultrasonographic gastrointestinal wall abnormalities in dogs with AP.

RETURN TO TOP

-- biopsy

The “gold standard” for diagnosing pancreatitis is a biopsy by making an incision through the abdominal wall. Alternatives to biopsies include a fine needle aspiration (cytologic evaluation), blood tests, enzyme assays, x-rays, and ultrasounds. Usually blood counts, pancreatic enzyme assays and x-rays are conducted in combination, as any one alone would be insufficient to accurately diagnose chronic pancreatitis.

RETURN TO TOP

Related Disorders

- exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI)

- mitral valve disease

- diabetes mellitus

- gastrointestinal disorders

- pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome (PPP)

- the serotonin connection

-- Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI)

See our webpage on EPI.

-- Mitral valve disease

There is evidence of a link between advanced stages of mitral valve disease and pancreatitis. In a January 2015 study of 62 dogs -- 40 with various stages of MVD and 22 healthy ones (none were cavaliers) -- South Korean researchers found an increase in serum canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI) concentrations with the worsening of heart failure signs in the affected dogs. They concluded that pancreatic injury is associated with congestive heart failure (CHF) caused by MVD. They acknowledged that there were limitations to the study, primarily due to the number of dogs and the extent of the assessment of pancreatitis in the dogs. Nevertheless, they stated:

"Despite these study limitations, our study results clearly suggest that the increased serum PLI concentration, to levels accepted as indicating pancreatitis, is a common comorbidity with congestive heart failure. Therefore, regular check-up for serum PLI level is warranted for early detection of pancreatitis from chronic heart diseases."

In a July 2019 article, South Korean researchers tested MVD-affected dogs in all ACVIM stages of MVD to evaluate any relationships between the progression of MVD and levels of lipase (and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide -- NT-proBNP). No cavaliers were included in the 84-dog study. They report finding that over a two-year period, NT-proBNP showed a strong positive correlation with increasing stage of heart disease; lipase showed a mild positive correlation with heart disease stage.

-- Diabetes mellitus

The end stage of chronic pancreatitis may result in diabetes mellitus, due to extensive destruction of pancreatic tissues. In a January 2015 report, UK author Lucy J. Davison has observed that cases of diabetes mellitus often accompany exocrine pancreatic inflammation. She states:

"However, the question remains as to whether the diabetes mellitus causes the pancreatitis or whether, conversely, the pancreatitis leads to diabetes mellitus – as there is evidence to support both scenarios. The concurrence of diabetes mellitus and pancreatitis has clinical implications for case management as such cases may follow a more difficult clinical course, with their glycaemic control being 'brittle' as a result of variation in the degree of pancreatic inflammation. Problems may also arise if abdominal pain or vomiting lead to anorexia. In addition, diabetic cases with pancreatitis are at risk of developing exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in the following months to years, which can complicate their management further."

-- Gastrointestinal disorders

See our separate webpage on gastrointestinal disorders, including hemorrhagic gastroenteritis (HGE). Pancreatitis has been determined to be a cause of HGE.

-- Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome (PPP)

Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome (PPP) is a very rare syndrome both in humans and dogs. Its primary signs are development of dead skin tissues and painful lesions, and swollen joints, typically around the hind legs. There may be only mild or no gastrointestional symptoms. Nonetheless, the patient also is diagnosed with chronic pancreatitis. Panniculitis is a condtion affecting the panniculus (the fat layer beneath the skin), resulting in painful bumps and inflammation. Polyarthritis means arthritic conditions affecting several joints at the same time.

In a September 2024 article, a 10 year old female cavalier had abscesses on her hind legs, fever, lethargy, lameness, and chronic pancreatitis. Sterile nodular panniculitis was diagnosed and was treated with steroids, but after 11 months, lesions spread on the skin and the lameness worsened. The dog was euthanized, and a post-mortem examination found a pancreatic adenocarcinoma and confirmed pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis (PPP), and osteomyelitis (bacterial infection of the bones and bone marrow).

-- The serotonin connection

Dr. Penny Watson of the University of Cambridge, who has been studying pancreatitis in cavaliers for many years, opined at a presentation in November 2014 the hypothesis that there may be a relationship between the serotonin carried by blood platelets through the vascular system to various organs, particularly the pancreas, the kidneys, the liver, the central nervous system, and the mitral valves of the heart, all causing scarring of and other damage to the tissues of these organs. She stated:

"We had a theory that these dogs have an increased propensity to produce scar tissue, and that in fact they are doing it in multiple organs. So, there is so link between some of these diseases. ... When we look at the central nervous system in dogs with syringomyelia histologically, we find more fibrosis around blood vessels than you would normally find in a normal dog. ... We don't know what's causing the scarring in the pancreas. There is something causing it, and it seems to be coming up the ducts because that's where a lot of this is happening. And actually my theory at the moment is that it has something to do with the duct bacteria. And that theory has developed after seeing not one or two, but actually four or five cavaliers with chronic pancreatitis who respond very well to antibiotic therapy, metronidazole therapy specifically. And that's the sort of antibiotic that we use for overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine, not the sort of antibiotic we use for other infections. And so I either think they've got gut bacteria coming up the duct, and perhaps their normal gut bacteria and it just that cavaliers' over-responding. Or, maybe there's something about their duct flora that's driving it, but I think there is a link there, somehow or another between the cavalier's gut flora and what's happening in the pancreas.

"Now why might they [cavaliers] be forming too much scar tissue? ... A current theory revolves around their platelets. Platelets are blood clotting cells. ... In cavaliers, about 50% of cavaliers in the UK have these macro-platelets, these jumbo platelets. ... Something in these cavaliers is stimulating these stellate cells to transform and produce lots of fibrous tissue. ... We noticed in cavaliers ... that there was a pattern of increased fibrosis in multiple organs, the kidneys particularly. Mitral valve disease isn't scarring. Mitral valve disease is myxomatous change. ... But the cells that produce that are valvular interstitial cells, and they are identical to the stellate cells in the pancreas. The current theory ... is that these little dogs might have something in their platelets that they are releasing when they are going through blood vessels into different organs that's tending to cause fibrosis. And our theory ... is that this might be serotonin, which is also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine, because platelets contain a bucket load of serotonin. ...

"We already know that some cavaliers have elevated levels of serotonin, that's been shown. We also already know that serotonin is central to converting those valvular interstitial cells into myofibroblasts. ... I think what was most compelling for me was the human side of it. There is a particular horrible syndrome in people called carcinoid syndrome. People who've got serotonin secreting tumors that they've got. ... They get pancreatic, liver, and kidney fibrosis and mitral valve disease. ... So in a nutshell, the hypothesis was these big floppy platelets release serotonin easily as they pass through vessels, leading to fibrosis in perivascular areas."

RETURN TO TOP

Treatment

Unless a specific cause has been determined, most cases of pancreatitis are treated to relieve the symptoms, especially abdominal pain. If the cause is known (more likely in acute cases than chronic ones), the treatment includes removing that cause.

Treatment of acute onset pancreatitis with IV fluids usually is administered, because fluids are needed to maintain the function of the pancreas and hydration. Most affected dogs are dehydrated. However, over-hydration must be avoided. Othere organs, especially the kidneys, liver, and respiratory system, must be monitored to avoid complications caused by the pancreatitis. Nutritional food also is essential early in the treatment process. Appetite stimulants may be necessary. Initially, a low fat diet is recommended.

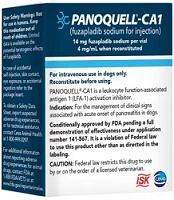

Fuzapladib sodium hydrate: In November 2022, the

USA's Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted conditional approval of

fuzapladib sodium hydrate (Panoquell-CA1) for injection for the

management of clinical signs associated with acute onset of pancreatitis

in dogs. Panoquell-CA1 is an injectable drug intended for use while the

dog is hospitalized for treatment of the disease. Fuzapladib sodium, the

active ingredient in Panoquell, has been approved since 2018 in Japan to

improve clinical signs in the acute phase of pancreatitis in dogs. The

FDA reviewed data associated with fuzapladib’s use in Japan as part of

its assessment of the application for conditional approval. Fuzapladib

has not been studied in dogs with cardiac, hepatic, or renal disease;

dogs less than 6 months old; or dogs that are pregnant, lactating, or

intended for breeding. Among the

reported possible adverse effects are: gastrointestinal effects (eg,

anorexia, diarrhea, hypersalivation), hepatopathy, jaundice, respiratory

tract effects (eg, pneumonia, tachypnea, dyspnea), cardiac effects (eg,

arrhythmia, hypertension, cardiac arrest), hyperthermia, pruritus, and

cerebral edema. Conditional approval also means that, when used according to the label,

the drug is safe and has a reasonable expectation of effectiveness. The

drug sponsor must meet the requirements for substantial evidence of

effectiveness within five years for full approval.

Fuzapladib sodium hydrate: In November 2022, the

USA's Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted conditional approval of

fuzapladib sodium hydrate (Panoquell-CA1) for injection for the

management of clinical signs associated with acute onset of pancreatitis

in dogs. Panoquell-CA1 is an injectable drug intended for use while the

dog is hospitalized for treatment of the disease. Fuzapladib sodium, the

active ingredient in Panoquell, has been approved since 2018 in Japan to

improve clinical signs in the acute phase of pancreatitis in dogs. The

FDA reviewed data associated with fuzapladib’s use in Japan as part of

its assessment of the application for conditional approval. Fuzapladib

has not been studied in dogs with cardiac, hepatic, or renal disease;

dogs less than 6 months old; or dogs that are pregnant, lactating, or

intended for breeding. Among the

reported possible adverse effects are: gastrointestinal effects (eg,

anorexia, diarrhea, hypersalivation), hepatopathy, jaundice, respiratory

tract effects (eg, pneumonia, tachypnea, dyspnea), cardiac effects (eg,

arrhythmia, hypertension, cardiac arrest), hyperthermia, pruritus, and

cerebral edema. Conditional approval also means that, when used according to the label,

the drug is safe and has a reasonable expectation of effectiveness. The

drug sponsor must meet the requirements for substantial evidence of

effectiveness within five years for full approval.

Mild cases of pancreatitis, with vomiting and dehydration, may require oral or intravenous fluids and pancreatic rest, meaning no solid food, followed by a change to a more appropriate diet. Hospitalization may be required to assure proper treatment and rest.

Antiemetics may be prescribed to reduce excessive vomiting, but they may have side effects which could increase pancreatic pain. A phenothiazine antiemetic such as chlorpromazine may avoid the additional pain, but it is not licensed for use by small animals. Cerenia (maropitant citrate) is an anti-nausea drug which is also a pain killer. Ondansetron, a 5-HT3 serotonergic antagonist, is another common medication for vomiting dogs.

Camostat mesilate, an oral protease inhibitor, has shown to be successful in rat studies to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production, markedly decrease microscopic signs of inflammation, and suppress fibrosis associated with chronic pancreatitis. It has been has been used clinically for the treatment of chronic pancreatitis in humans in Japan. In an April 2017 U.S. patent application, the inventors are seeking a patent to use camostat mesilate to treat dogs diagnosed with chronic panreatitis. In one study discussed in the application, two cavaliers were included among the dogs being treated.

Since pancreatitis is very painful, affected dogs may be given analgesia such as Paracetamol (acetaminophen)* or even a morphine agonist or partial agonist, particularly buprenorphine (Buprenex, Temgesic sublingual), or butophanol tartrate (Torbutrol, Stadol, Torbugesic-SA, Torbugesic). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) usually are not given because of an increased risk of gastroduodenal ulceration and a potential renal failure reaction. Vetergesic may be given by injection for severe pain. NSAIDs should not be administered without supervision by a veterinarian. The US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) warns about the dangers of using NSAIDs here on its website.

* Paracetamol (acetaminophen) can be toxic to dogs and must be given only under strict veterinary supervision.

While hospitalized, affected dogs may receive artificial nutrtion by enteral feeding (through a tube into the stomach or small intestine), which reportedly has been found to provide an early return to voluntary intake of food orally, to avoid the effects of delayed feedings upon the dogs' gastrointestinal systems.

A long-term low fat diet, along with supplementary enzymes, likely will be recommended. However, whether to feed the pancreatitis patient or not, and what to feed that patient, is so controversial that in this November 2016 article, the author reaches no specific conclusion. All dogs need fats in their diets. Less processed fats -- mainly uncooked fats rather than cooked fats -- appear to not cause or contribute to pancreatits.

Other veterinary nutritionists report that highly processed dry foods with high percentages of carbohydrates are either the cause of some cases or aggravate the dog's condition. They advise to give the pancreas a rest by initially fasting for one to two days. Then, follow up with small quantity meals -- 3 to 5 times a day -- instead of the usual two meals. Finally, they recommend avoiding dry foods entirely because they are highly processed and are very high in carbohyrates.

Severe cases, in which the tissue has begun to die (necrotize) and the liver has been affected, are unlikely to recover. However, in a 2009 review of the use of probiotics in veterinary practice, Dr. Susan G. Wynn reports that probiotics may benefit dogs with acute (but not chronic) necrotizing pancreatitis. She stated:

"Probiotic organisms appear to improve the intestinal barrier, which prevents bacterial translocation, and lactic acid–producing bacteria can suppress the inflammation that makes systemic inflammation response syndrome such a deadly condition in patients with acute pancreatitis. Investigators have conducted studies in dogs with experimentally induced severe pancreatitis. Affected dogs have been provided nutrients parenterally as well as elemental enteral nutrition or dietary supplementation with probiotics."

Dr. Penny Watson reported, in a November 2014 presentation, seeing some cavaliers with chronic pancreatitis "respond very well to antibiotic therapy, metronidazole* therapy specifically."

* Metronidazole (Flagyl) may cause adverse events in dogs hypersensitive to it. See Metronidazole Risks.

RETURN TO TOP

What You Can Do

Consider adding plant enzymes and probiotics to your dog's diet.

RETURN TO TOP

Research News

September 2024:

Cavalier is diagnosed with pancreatitis, panniculitis,

polyarthritis syndrome (PPP).

In

a

September 2024 article, a team of Auburn University clinicians (Abby

Hagelskamp [right], Amelia G. White, Jeremy Gallman, Cierra

Starbird, Rachel L. A. L. T. Neto) report a case study of a 10 year old

female cavalier King Charles spaniel which had abscesses on her hind

legs, fever, lethargy, lameness, and chronic pancreatitis. Sterile

nodular panniculitis was diagnosed and was treated with steroids, but

after 11 months, lesions spread on the skin and the lameness worsened.

The dog was euthanized, and a post-mortem examination found a pancreatic

adenocarcinoma (a malignant glandular tumor) and confirmed

pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis (PPP), and osteomyelitis

(bacterial infection of the bones and bone marrow).

In

a

September 2024 article, a team of Auburn University clinicians (Abby

Hagelskamp [right], Amelia G. White, Jeremy Gallman, Cierra

Starbird, Rachel L. A. L. T. Neto) report a case study of a 10 year old

female cavalier King Charles spaniel which had abscesses on her hind

legs, fever, lethargy, lameness, and chronic pancreatitis. Sterile

nodular panniculitis was diagnosed and was treated with steroids, but

after 11 months, lesions spread on the skin and the lameness worsened.

The dog was euthanized, and a post-mortem examination found a pancreatic

adenocarcinoma (a malignant glandular tumor) and confirmed

pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis (PPP), and osteomyelitis

(bacterial infection of the bones and bone marrow).

March 2022:

Gastrointestinal wall changes were found in dogs diagnosed with

acute pancreatitis, in UK study.

In

a

March 2022 article, UK veterinary researchers (Joshua J. Hardwick

[right], Elizabeth J. Reeve, Melanie J. Hezzell, Jenny A.

Reeve) studied 66 dogs diagnosed with acute pancreatitis (AP), including

3 cavaliers (4.55%). They sought to determine by ultrasound any

gastrointestinal (GI) wall changes in the dogs, especially whether the

presence of neutrophilia, left shift, or toxic neutrophils would serve

as markers of increased severity of inflammation.They found that 31 of

the dogs (47%) had ultrasonographic gastrointestinal wall changes, most

commonly in the duodenum. Of the dogs with gastrointestinal wall

changes, 23 (74.2%) had wall thickening, 19 (61.3%) had abnormal wall

layering, and 11 (35.5%) had wall corrugation. Only increased heart

rates was an independent predictor of gastrointestinal wall changes, but

because of possible other factors, they considered heart rate unlikely

to be useful in indicating whether GI wall changes are likely to be

present. They concluded that ultrasonographic gastrointestinal wall

changes were relatively common in this population of dogs with AP and

that the results may aid clinicians in interpreting ultrasonographic

gastrointestinal wall abnormalities in dogs with AP.

In

a

March 2022 article, UK veterinary researchers (Joshua J. Hardwick

[right], Elizabeth J. Reeve, Melanie J. Hezzell, Jenny A.

Reeve) studied 66 dogs diagnosed with acute pancreatitis (AP), including

3 cavaliers (4.55%). They sought to determine by ultrasound any

gastrointestinal (GI) wall changes in the dogs, especially whether the

presence of neutrophilia, left shift, or toxic neutrophils would serve

as markers of increased severity of inflammation.They found that 31 of

the dogs (47%) had ultrasonographic gastrointestinal wall changes, most

commonly in the duodenum. Of the dogs with gastrointestinal wall

changes, 23 (74.2%) had wall thickening, 19 (61.3%) had abnormal wall

layering, and 11 (35.5%) had wall corrugation. Only increased heart

rates was an independent predictor of gastrointestinal wall changes, but

because of possible other factors, they considered heart rate unlikely

to be useful in indicating whether GI wall changes are likely to be

present. They concluded that ultrasonographic gastrointestinal wall

changes were relatively common in this population of dogs with AP and

that the results may aid clinicians in interpreting ultrasonographic

gastrointestinal wall abnormalities in dogs with AP.

October 2019:

Koreans find direct correlation between lipase levels in

progression of mitral valve disease in dogs. In a

July 2019 article, a team of Korean veterinary researchers (Jun-Seok

Park, Jae-Hong Park, Kyoung-Won Seo, Kun-Ho Song [right]) tested MVD-affected

dogs in all ACVIM stages of MVD to evaluate any relationships between

the progression of MVD and levels of lipase (and N-terminal pro B-type

natriuretic peptide -- NT-proBNP). No cavaliers were included in the

84-dog study. They report finding that over a two-year period, NT-proBNP

showed a strong positive correlation with increasing stage of heart

disease; lipase showed a mild positive correlation with heart disease

stage.

October 2019:

Koreans find direct correlation between lipase levels in

progression of mitral valve disease in dogs. In a

July 2019 article, a team of Korean veterinary researchers (Jun-Seok

Park, Jae-Hong Park, Kyoung-Won Seo, Kun-Ho Song [right]) tested MVD-affected

dogs in all ACVIM stages of MVD to evaluate any relationships between

the progression of MVD and levels of lipase (and N-terminal pro B-type

natriuretic peptide -- NT-proBNP). No cavaliers were included in the

84-dog study. They report finding that over a two-year period, NT-proBNP

showed a strong positive correlation with increasing stage of heart

disease; lipase showed a mild positive correlation with heart disease

stage.

February 2018:

Mississippi State Univ. researchers compare SNAP cPL, Spec cPL,

VetScan cPL, and Precision PSL enzyme assays for accuracy in diagnosing

pancreatitis in dogs.

In a

February 2018 article, a team of five board-certified small animal

veterinary internists, led by Mississippi State University researchers

(Harry Cridge [right], A.G. MacLeod, G.E. Pachtinger, A.J. Mackin, A.M. Sullivant,

J.M. Thomason , T.M. Archer, K.V. Lunsford, K. Rosenthal, R.W. Wills),

compared the accuracy of four diagnostic assays -- SNAP canine

pancreatic lipase (cPL), specific cPL (Spec cPL), VetScan cPL Rapid

Test, and Precision PSL -- for pancreatitis in a group of 50 dogs. None

were cavalier King Charles spaniels. Their goal was to determine the

level of agreement among each of the four assays and a clinical

suspicion score, level of agreement among the assays, and sensitivity

and specificity of each assay in a clinically relevant group of dogs.

The clinical suspicion scoring was conducted by the five internists, on

a scale of 0 (the patient almost certainly did not have pancreatitis) to

2 (the patient almost certainly had pancreatitis) for each of the fifty

dogs and then averaged.

In a

February 2018 article, a team of five board-certified small animal

veterinary internists, led by Mississippi State University researchers

(Harry Cridge [right], A.G. MacLeod, G.E. Pachtinger, A.J. Mackin, A.M. Sullivant,

J.M. Thomason , T.M. Archer, K.V. Lunsford, K. Rosenthal, R.W. Wills),

compared the accuracy of four diagnostic assays -- SNAP canine

pancreatic lipase (cPL), specific cPL (Spec cPL), VetScan cPL Rapid

Test, and Precision PSL -- for pancreatitis in a group of 50 dogs. None

were cavalier King Charles spaniels. Their goal was to determine the

level of agreement among each of the four assays and a clinical

suspicion score, level of agreement among the assays, and sensitivity

and specificity of each assay in a clinically relevant group of dogs.

The clinical suspicion scoring was conducted by the five internists, on

a scale of 0 (the patient almost certainly did not have pancreatitis) to

2 (the patient almost certainly had pancreatitis) for each of the fifty

dogs and then averaged.

They found that:

• The level of agreement between individual diagnostic tests for pancreatitis and the clinical suspicion score was good.

• The level of agreement among the four diagnostic assays for pancreatitis was greater than the level of agreement between an individual diagnostic test and the clinical suspicion score.

• No single assay had high enough diagnostic specificity to conclusively diagnose pancreatitis based on a single test result, meaning that a combination of signalment, physical examination, blood tests, a pancreatic lipase test, and ideally, abdominal ultrasound examination, may be the most practical means of establishing a definitive diagnosis of clinical pancreatitis in dogs.

The study was funded by Abaxis Inc., the manufacturer of the VetScan cPL Rapid Test.

April

2017:

Inventors seek US patent for chronic pancreatitis drug camostat

mesilate. In an

April 2017 U.S. patent application, the inventors (Long-Shiuh Chen,

Diana Wood, Aidan Nuttall) are seeking a

patent to use camostat mesilate to treat dogs diagnosed with chronic

panreatitis. In one study discussed in the application, two cavaliers

were included among the dogs being treated. Camostat mesilate is an oral

protease inhibitor which has been shown to be successful in rat studies

to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production, markedly decrease

microscopic signs of inflammation, and suppress fibrosis associated with

chronic pancreatitis. It has been has been used clinically for the

treatment of chronic pancreatitis in humans in Japan.

April

2017:

Inventors seek US patent for chronic pancreatitis drug camostat

mesilate. In an

April 2017 U.S. patent application, the inventors (Long-Shiuh Chen,

Diana Wood, Aidan Nuttall) are seeking a

patent to use camostat mesilate to treat dogs diagnosed with chronic

panreatitis. In one study discussed in the application, two cavaliers

were included among the dogs being treated. Camostat mesilate is an oral

protease inhibitor which has been shown to be successful in rat studies

to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production, markedly decrease

microscopic signs of inflammation, and suppress fibrosis associated with

chronic pancreatitis. It has been has been used clinically for the

treatment of chronic pancreatitis in humans in Japan.

November 2016:

To

feed or not to feed the pancreatitis patient?

Who

knows?

When a veterinary

journal article title is in the form of a question,

you can be assured the author has no answer. In a

November 2016 article, a University of Florida veterinary

nutritionist (Justin Shmalberg, right) asks that question and ends up

raising

even more questions in his conclusion. For example, he states:

journal article title is in the form of a question,

you can be assured the author has no answer. In a

November 2016 article, a University of Florida veterinary

nutritionist (Justin Shmalberg, right) asks that question and ends up

raising

even more questions in his conclusion. For example, he states:

"Unfortunately, current knowledge is inadequate to provide a strong evidence-based recommendation on when and how to feed many patients."

"Dietary fat restriction appears to be a critical part of successful management of chronic disease in dogs, but its role in acute pancreatitis is less clear".

"The definition of a low fat diet for patients with pancreatitis is not well established".

January 2016:

Pancreatic lesions were found in 51.9% of post-mortem samples of

cavaliers in UK study.

In an

April 2016 article, UK

researchers (Kent, Andrew C. C. [right]; Constantino-Casas, Fernando; Rusbridge,

Clare; Corcoran, Brendan; Carter, Margaret; Ledger, Tania; Watson, Penny

J.) searched for pancreatic, hepatic (liver) and renal (kidney) lesions

in post-mortem samples from 54 cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCSs). The

rate of diagnosis of pancreatic disease prior to death was in 25% of the

CKCSs, but the post-mortem examination found evidence of chronic

pancreatitis in 51.9% of the dogs, and the dogs' ages correlated with

severity of disease. The researchers report that this evidence suggested

that chronic pancreatitis is a progressive condition. They concluded

that pancreatic lesions are common in the breed, and that clinicians should

be aware of this when presented with clinical cases.

In an

April 2016 article, UK

researchers (Kent, Andrew C. C. [right]; Constantino-Casas, Fernando; Rusbridge,

Clare; Corcoran, Brendan; Carter, Margaret; Ledger, Tania; Watson, Penny

J.) searched for pancreatic, hepatic (liver) and renal (kidney) lesions

in post-mortem samples from 54 cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCSs). The

rate of diagnosis of pancreatic disease prior to death was in 25% of the

CKCSs, but the post-mortem examination found evidence of chronic

pancreatitis in 51.9% of the dogs, and the dogs' ages correlated with

severity of disease. The researchers report that this evidence suggested

that chronic pancreatitis is a progressive condition. They concluded

that pancreatic lesions are common in the breed, and that clinicians should

be aware of this when presented with clinical cases.

November 2015: Japanese clinicians find Fuji Dri-Chem lipase aided diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. In a November 2015 article, a group of Japanese researchers examined the use of a new diagnostic laboratory test, Fuji Dri-Chem lipase (FDP lip), compared to amylase, in diagnosing acute pancreatitis (AP). They found that among 64 dogs, activities of amylase and FDC lip were significantly higher in the AP group than in the nonpancreatic disease (NP) group. They report that the sensitivity of FDP lip activity for diagnosing AP was 100%. They did not compare the FDC lip with IDEXX's SNAP cPL test. They concluded that "the measurement of FDC lip activity appears useful for diagnosing AP."

July 2015: Spanish study shows anticonvulsants may cause increase in canine pancreas-specific lipase but not acute pancreatitis. In a July 2015 study, Spanish researchers (Mariana Teles, Antonio Meléndez-Lazo, Jaume Rodón, Josep Pastor) report finding that some dogs treated with anticonvulsants (phenobarbital and potassium bromide) may show an increase in canine pancreas-specific lipase, but its increase may not be associated with severe acute pancreatitis.

February 2015: Swedish study finds serotonin levels increase in spayed bitches. In a February 2015 report by veterinary doctoral student Elin Larsson, she studied 7 female dogs and 3 males, including on cavalier King Charles spaniel male, she found that "Among the bitches, the serotonin levels tended to increase after castration [sic]. The male dogs were few in number and no obvious changes in hormone levels were shown."

January 2015: Korean researchers find link between advanced MVD and pancreatitis. In a January 2015 study of 62 dogs -- 40 with various stages of MVD and 22 healthy ones (none were cavaliers) -- a team of South Korean researchers (D. Han, R. Choi, and C. Hyun) found an increase in serum canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI) concentrations with the worsening of heart failure signs in the affected dogs. They concluded that pancreatic injury is associated with congestive heart failure (CHF) caused by MVD. They acknowledged that there were limitations to the study, primarily due to the number of dogs and the extent of the assessment of pancreatitis in the dogs. Nevertheless, they stated:

""Despite these study limitations, our study results clearly suggest that the increased serum PLI concentration, to levels accepted as indicating pancreatitis, is a common comorbidity with congestive heart failure. Therefore, regular check-up for serum PLI level is warranted for early detection of pancreatitis from chronic heart diseases."

January 2015: "Pancreatitis

in Cavaliers: What is it and what can I do about it?" A DVD

(right)

of

a seminar presented by Dr. Penny Watson of the University of Cambridge,

UK in November 2014, is available for purchase from Cavalier

Matters.

of

a seminar presented by Dr. Penny Watson of the University of Cambridge,

UK in November 2014, is available for purchase from Cavalier

Matters.

In her presentation, Dr. Watson reported finding a very high prevalence of chronic pancreatitis in cavaliers. Specifically, she said:

"What we've found, just looking at the histology, is that there is a very high prevalence, and that by the time we get to dogs of 11, 12, 13, I would be surprised to see a normal pancreas. And I would say the prevalence of chronic pancreatitis in cavaliers mimics mitral valve disease. ... I would say about 80%. ... Like mitral valve disease, it is a disease of aging. It is not so common in younger dogs."

She also discussed a current hypothesis which links mitral valve disease and pancreatitis and kidney disease in cavaliers through the secretion of serotonin by the cavaliers' blood platelets. She stated:

"We noticed in cavaliers ... that there was a pattern of increased fibrosis in multiple organs, the kidneys particularly. Mitral valve disease isn't scarring. Mitral valve disease is myxomatous change. ... But the cells that produce that are valvular interstitial cells, and they are identical to the stellate cells in the pancreas. The current theory ... is that these little dogs might have something in their platelets that they are releasing when they are going through blood vessels into different organs that's tending to cause fibrosis. And our theory ... is that this might be serotonin, which is also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine, because platelets contain a bucket load of serotonin. ... We already know that some cavaliers have elevated levels of serotonin, that's been shown. We also already know that serotonin is central to converting those valvular interstitial cells into myofibroblasts. ... I think what was most compelling for me was the human side of it. There is a particular horrible syndrome in people called carcinoid syndrome. People who've got serotonin secreting tumors that they've got. ... They get pancreatic, liver, and kidney fibrosis and mitral valve disease. ... So in a nutshell, the hypothesis was these big floppy platelets release serotonin easily as they pass through vessels, leading to fibrosis in perivascular areas."

January 2015: Which disorder causes the other? Diabetes mellitus or exocrine pancreatic inflammation? In a January 2015 report, UK author Lucy J. Davison has observed that cases of diabetes mellitus often accompany exocrine pancreatic inflammation. She states:

"However, the question remains as to whether the diabetes mellitus causes the pancreatitis or whether, conversely, the pancreatitis leads to diabetes mellitus – as there is evidence to support both scenarios. The concurrence of diabetes mellitus and pancreatitis has clinical implications for case management as such cases may follow a more difficult clinical course, with their glycaemic control being 'brittle' as a result of variation in the degree of pancreatic inflammation. Problems may also arise if abdominal pain or vomiting lead to anorexia. In addition, diabetic cases with pancreatitis are at risk of developing exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in the following months to years, which can complicate their management further."

January

2014:

Dr. Penny Watson looks for ties between fibrosis in MVD, SM, and chronic

pancreatitis in CKCSs.

Dr. Penny Watson (right) of UK's Cambridge University's veterinary school is

spearheading a new study into whether several of the CKCS breed's hereditary

health problems are the result of the same genetic defect. Specifically, she

intends to explore the possibility that disparate cavalier diseases,

including mitral valve disease (MVD), syringomyelia (SM), and chronic

pancreatitis are connected at the cellular level by unusual patterns of

fibrotic changes. "Pronounced perivescular fibrosis", a feature in dogs with

chronic pancreatitis, also has been tied to a condition of the central

nervous system in cavaliers with SM. Dr. Watson has suggested that

deterioration of cavaliers' mitral valves also may be a result of a process

connected to the causes of fibrosis.

pancreatitis in CKCSs.

Dr. Penny Watson (right) of UK's Cambridge University's veterinary school is

spearheading a new study into whether several of the CKCS breed's hereditary

health problems are the result of the same genetic defect. Specifically, she

intends to explore the possibility that disparate cavalier diseases,

including mitral valve disease (MVD), syringomyelia (SM), and chronic

pancreatitis are connected at the cellular level by unusual patterns of

fibrotic changes. "Pronounced perivescular fibrosis", a feature in dogs with

chronic pancreatitis, also has been tied to a condition of the central

nervous system in cavaliers with SM. Dr. Watson has suggested that

deterioration of cavaliers' mitral valves also may be a result of a process

connected to the causes of fibrosis.

The CKCS breed's documented overabundance of serotonin, a neurotransmitter protein, has been identified as a plausible mechanism which may trigger the development of fibrotic changes in the heart's valves. Her study entails establishing primary stellate cell (SC) cultures from CKCS and define 5HT receptor subtype expression. Stellate cell (SC) activation is a key event in the development of hepatic and pancreatic fibrosis. Serotonin has been shown to activate SCs via 5HT receptors. The study is measuring the response of these cells to serotonin and other stimulators of fibrosis. She then intends to attempt to block SC activation in vitro using 5HTreceptor antagonists. Increased understanding of the factors driving fibrosis will be of benefit to the CKCS and may allow a drug trial in the breed.

March 2013: UK researcher seeks breakthroughs in understanding chronic pancreatitis in CKCSs. Dr. Penny Watson of the University of Cambridge is working closely with UK breeders of cavaliers to better understand the cause of chronic pancreatitis (CP) in the breed.* Over the past decade, she has published four research papers about CP, noting in the latter three its high prevalence in the CKCS. She also has found that the pathology of CP in the cavalier has a distinctive appearance. She said recently that "I hope we will soon be able to make some breakthroughs in understanding this disease better."

* See her 2004 report, her 2005 report, her 2007 report, and her 2012 report.

July

2012: Surprise! I DEXX finds that its SNAP and

SPEC tests are the best for diagnosing acute pancreatitis. In a

July 2012 report of a comparison

of various cPLI tests on 84 dogs, the researchers found that:

DEXX finds that its SNAP and

SPEC tests are the best for diagnosing acute pancreatitis. In a

July 2012 report of a comparison

of various cPLI tests on 84 dogs, the researchers found that:

"SNAP and SPEC have higher sensitivity for diagnosing clinical AP [acute pancreatitis] than does measurement of serum amylase or lipase activity. A positive SPEC or SNAP has a good positive predictive value (PPV) in populations likely to have AP and a good negative predictive value (NPV) when there is low prevalence of disease."

Of course, the study was sponsored by IDEXX, the producer of SNAP and SPEC tests. However, that fact is not intended to take anything away from the value of these two tests.

May 2011: Cavaliers and Jack Russells may be predisposed. US researchers report in a May 2011 study that cavalier King Charles spaniels are one of only two breeds which may be predisposed to chronic pancreatitis which can result in destruction of acinar cells. The other breed is the Jack Russell terrier (Parson Russell terrier in AKC).

March

2009: Probiotics may benefit dogs with acute necrotizing

pancreatitis. In a March 2009

review

of probiotics in veterinary practice, Dr. Susan G. Wynn

(right) reports that probiotics may benefit dogs with acute necrotizing

pancreatitis. She writes:

review

of probiotics in veterinary practice, Dr. Susan G. Wynn

(right) reports that probiotics may benefit dogs with acute necrotizing

pancreatitis. She writes:

"Probiotic organisms appear to improve the intestinal barrier, which prevents bacterial translocation, and lactic acid–producing bacteria can suppress the inflammation that makes systemic inflammation response syndrome such a deadly condition in patients with acute pancreatitis. Investigators have conducted studies in dogs with experimentally induced severe pancreatitis. Affected dogs have been provided nutrients parenterally as well as elemental enteral nutrition or dietary supplementation with probiotics."

RETURN TO TOP

Related Links

RETURN TO TOP

Veterinary Resources

Control of Canine Genetic Diseases. Padgett, G.A., Howell Book House 1998, pp. 198-199, 232.

Pancreatitis in the dog: dealing with a spectrum of disease. Penny Watson. In Practice, Feb 2004; 26:64-77. Quote: "PANCREATITIS - whether it be acute or chronic - is a relatively common, but often misdiagnosed, problem in dogs. It is associated with a systemic inflammatory response which, in severe cases, can result in the development of multiorgan failure, diffuse intravascular coagulation and death. Classical acute pancreatitis is often straightforward to diagnose, but this only represents one end of a wide spectrum of disease. Milder and/or more chronic forms of the condition are not so easily recognised, but can cause significant pain and reduce the quality of life of an animal. There is no single diagnostic test with 100 per cent sensitivity and specificity for the disease, apart from biopsy which is relatively invasive and, hence, not often indicated. Treatment recommendations depend on the severity of the disease and range from conservative management at home to referral for intensive care. The causes of pancreatitis in dogs are usually unknown. Therefore, therapy tends to be symptomatic and non-specific. The potential long-term sequelae of chronic pancreatitis in dogs are largely uninvestigated, but can include the development of diabetes mellitus and/or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. This article discusses the potential causes, diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic pancreatitis in dogs."

Validation and diagnostic efficacy of a lipase assay using the substrate 1,2-o-dilauryl-rac-glycero glutaric acid-(6′methyl resorufin)-ester for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in dogs. Roberta Graca, Joanne Messick, Sheila McCullough, Anne Barger, Walter Hoffmann. Vet. Clin. Pathol. March 2005;34(1):39-43. Quote: Background: Increased serum lipase activity has been used historically to support the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, a common disease in dogs. Most of the lipase assays that are currently in use lack optimum sensitivity and specificit-(6′-methylresorufin) ester (DGGR) assay for determination of lipase activity in canine serum and 2) compare results, reference intervals, sensitivity, and specificity of the DGGR assay with a standard 1,2-diglyceride (1,2 DiG) assay for diagnosing acute pancreatitis in dogs. Methods: Precision, linearity, and interference studies were performed for method validation on a Hitachi 911 analyzer. Lipase results from the DGGR and 1,2 DiG assays were compared by linear regression analysis. Sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic efficacy were determined for both assays on a population of 30 dogs, 15 of which had acute pancreatitis based on history, clinical signs, and ultrasound findings. Results: Within-run and within-day coefficients of variation (CVs) were low (<3%), with higher day-to-day CVs (≤14 %). The assay was linear between 8 and 2792 U/L. No significant interference by hemolysis and lipemia was found. Poor correlation was found between the assays (rs= 0.84). The lipase reference interval was 8–120 U/L for the DGGR assay and 30–699 U/L for the 1,2 DiG assay. Sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of pancreatitis were 93% and 53%, respectively, for the DGGR assay and 60% and 73% for the 1,2 DiG assay. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis showed similar areas under the curve. Conclusions: On the basis of this study, the DGGR method is considered adequate for assaying serum lipase activity in dogs. The high sensitivity of the DGGR assay suggests it may be a useful screening test for canine pancreatitis.

Prevalence of Chronic Pancreatitis at Post Mortem Examination in an Unselected Population of First Opinion Dogs. PJ Watson, A Roulois, P Johnston, H Thompson, ME Herrtage. ECVIM 2005 Symposium Absract # 69. J.Vet.Intern. Med.;19(6).Quote: "The prevalence of chronic pancreatitis (CP) dogs is unknown. Previous studies have focused on acute pancreatitis and/or have used a highly biased and selected population of second opinion and critical care cases. This study aimed to assess the prevalence of chronic pancreatitis in an unselected population of first opinion dogs. Sections were obtained from 100 consecutive canine post mortems presented to Glasgow Veterinary School from surrounding first opinion practices. Most dogs were assessed as middle-aged to old. In each case, 3 sections of pancreas were taken: one from each limb and one from the body. Sections were preserved in formalin and stained with H&E and Sirius red. They were examined histologically, blind to signalment. Clinical details were not available. The dogs were grouped according to histological findings: (a) sections too autolysed to interpret; (b) no abnormalities visible; (c) non specific/non significant changes; (d) chronic or acute-on-chronic pancreatitis; (e) acute pancreatitis with no chronic changes and (f) other disease. Prevalence of each group was calculated and relative risk of CP and autolysis were calculated for different breeds. Prevalence of autolysis was 27%, a shortcoming of this type of study. Autolysis was common in large breed dogs due to slow cooling of core temperature (e.g German shepherd dogs relative risk of autolysis 3.8) so relative risk of CP could not be calculated in large breeds. The pancreas had no histological abnormalities in only 13% of dogs. Non specific changes were observed in 24% of dogs. Acute pancreatitis had a low prevalence of 2%. The prevalence of CP was 29% and breeds with a high relative risk included Cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCS): relative risk 4.1 and Jack Russell terriers: relative risk 2.4. 6/6 CKCS had CP, with 1/6 having end stage disease and 1/6 having concurrent pancreatic neoplasia. The lesions observed are likely to correlate with clinical disease: one out of four published cases of end stage CP with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) was a CKCS and a further 2/7 biopsy-confirmed cases of chronic pancreatitis seen at the Queen’s Veterinary School Hospital since 2002 were CKCS, both of which had EPI and one of which had diabetes mellitus. We conclude that CP is common in the first opinion dog population and that, like in the liver, end stage disease can be considered as a distinct clinically significant entity. There are strong breed-associations in CKCS and JRT, suggesting a possible genetic basis to the disease in these breeds."

Diagnosing and Treating Pancreatitis: A roundtable discussion. David A. Williams, Jörg M. Steiner, H. Mark Saunders, David Twedt, Benita von Dehn. IDEXX Learning Center. 2006.

Prevalence and breed distribution of chronic pancreatitis at post-mortem examination in first-opinion dogs. P. J. Watson, A. J. A. Roulois, T. Scase, P. E. J. Johnston, H. Thompson, and M. E. Herrtage. J Small Animal Prac (2007) 48:609–618. Quote: Quote: "Objectives: To assess the prevalence of canine chronic pancreatitis in first-opinion practice and identify breed associations or other risk factors. Methods: Three sections of pancreas were taken from 200 unselected canine post-mortem examinations from first-opinion practices. Sections were graded for inflammation, fibrosis and other lesions. Prevalence and relative risks of chronic pancreatitis and other pancreatic diseases were calculated. Results: The prevalence of chronic pancreatitis was 34 per cent omitting the autolysed cases. Cavalier King Charles spaniels, collies and boxers had increased relative risks of chronic pancreatitis; cocker spaniels had an increased relative risks of acute and chronic pancreatitis combined. Fifty-seven per cent of cases of chronic pancreatitis were classified histologically as moderate or marked. Forty-one per cent of cases involved all three sections. Dogs with chronic pancreatitis were more commonly female and overweight, but neither factor increased the relative risk of chronic pancreatitis. There were breed differences in histological appearances and 24·5 per cent of cases were too autolysed to interpret with an increased relative risk of autolysis in a number of large breeds. Clinical Significance: Chronic pancreatitis is a common, under-estimated disease in the first-opinion dog population with distinctive breed risks and histological appearances."

Prognostic Factors in Canine Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency: Prolonged Survival is Likely if Clinical Remission is Achieved. Daniel J. Batchelor, Peter-John M. Noble, Rebecca H. Taylor, Peter J. Cripps, and Alexander J. German. J Vet Intern Med 2007;21:54–60. Quote: "Background: Response to therapy in canine exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) varies considerably, making it difficult to determine prognosis for individual patients. Hypothesis: Response to initial treatment (RIT) and survival are affected by signalment, clinical variables, and herapeutic regimen employed. Animals: Client-owned dogs diagnosed with EPI between 1990 and 2002 were included in this study. Methods: The study comprised a retrospective, questionnaire-based review. Results: One hundred seventy-eight completed questionnaires were returned [16 cavalier King Charles spaniels]]. RIT was good in 60% of treated dogs, partial in 17%, and poor in 23%. On univariate analysis, dogs that received antibiotics (P 5 .037) or had high serum folate concentration (P 5 .037) had a poorer RIT. On multivariate analysis, there were no strong predictors of good RIT. Nineteen percent of treated dogs were euthanized within 1 year, but overall median survival time for treated dogs was 1919 days. No clear benefit of changing to a fat-restricted diet could be demonstrated, but marked hypo-cobalaminemia (,100 ng/L) was associated with shorter survival (P 5 .012). Use of uncoated pancreatic enzyme supplements, antibacterials, or H2 antagonists was not associated with longer survival. Breed, sex, age at diagnosis (#4 years or .4 years), and clinical signs at diagnosis also made no difference. Conclusions and Clinical Importance: Long-term prognosis in canine EPI is favorable for dogs that survive the initial treatment period. Although there are few predictors of good RIT or long-term survival, severe cobalamin deficiency is associated with shorter survival. Therefore, parenteral cobalamin supplementation should be considered when hypocobalaminemia is documented."

Breed Associations for Canine Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency. Daniel J. Batchelor, Peter-John M. Noble, Peter J. Cripps, Rebecca H. Taylor, Lynn McLean, Marion A. Leibl, Alexander J. German. J. Vet. Intern. Med. March 2007;21(2):207–214. Quote: Background: Knowledge of breed associations is valuable to clinicians and researchers investigating diseases with a genetic basis. Hypothesis: Among symptomatic dogs tested for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) by canine trypsin-like immunoreactivity (cTLI) assay, EPI is common in certain breeds and rare in others. Some breeds may be overrepresented or underrepresented in the population of dogs with EPI. Pathogenesis of EPI may be different among breeds. Animals: Client-owned dogs with clinical signs, tested for EPI by radioimmunoassay of serum cTLI, were used. Methods: In this retrospective study, results of 13,069 cTLI assays were reviewed. Results: An association with EPI was found in Chows, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS), Rough-Coated Collies (RCC), and German Shepherd Dogs (GSD) (all P , .001). Chows (median, 16 months) were younger at diagnosis than CKCS (median, 72 months, P , .001), but not significantly different from GSD (median, 36 months, P 5 .10) or RCC (median, 36 months, P 5 .16). GSD (P , .001) and RCC (P 5 .015) were younger at diagnosis than CKCS. Boxers (P , .001), Golden Retrievers (P , .001), Labrador Retrievers (P , .001), Rottweilers (P 5 .022), and Weimaraners (P 5 .002) were underrepresented in the population with EPI. Conclusions and Clinical Implications: An association with EPI in Chows has not previously been reported. In breeds with early-onset EPI, immune-mediated mechanisms are possible or the disease may be congenital. When EPI manifests later, as in CKCS, pathogenesis is likely different (eg, secondary to chronic pancreatitis). Underrepresentation of certain breeds among dogs with EPI has not previously been recognized and may imply the existence of breed-specific mechanisms that protect pancreatic tissue from injury. ... There are strong breed associations with CP in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS) and Jack Russell Terrier. ... Breeds with increased prevalence: ... Cavalier King Charles Spaniel:: Number Affected [with EPI]: 64; Number Tested: 243.

Platelet function in dogs: breed differences and effect of acetylsalicylic acid administration. Line A. Nielsen, Nora E. Zois, Henrik D. Pedersen, Lisbeth H. Olsen, Inge Tarnow. Veterinary Clinical Pathology. September 2007;36(3):267-273. Quote: "Background: Clinical studies investigating platelet function in dogs have had conflicting results that may be caused by normal physiologic variation in platelet response to agonists. Objectives: The objective of this study was to investigate platelet function in clinically healthy dogs of 4 different breeds by whole-blood aggregometry and with a point-of-care platelet function analyzer (PFA-100), and to evaluate the effect of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) administration on the results from both methods. Methods: Forty-five clinically healthy dogs (12 Cavalier King Charles Spaniels [CKCS], 12 Cairn Terriers, 10 Boxers, and 11 Labrador Retrievers) were included in the study. Platelet function was assessed by whole-blood aggregation with ADP (1, 5, 10, and 20 μM) as agonist and by PFA-100 using collagen and epinephrine (Col + Epi) and Col + ADP as agonists. Plasma thromboxane B2 concentration was determined by an enzyme immunoassay. To investigate the effect of ASA, 10 dogs were dosed daily (75 or 250 mg ASA orally) for 4 consecutive days. Results: A higher platelet aggregation response was found in CKCS compared to the other breeds. Longer PFA-100 closure time (Col + Epi) was found in Cairn Terriers compared to Boxers. Plasma thromboxane B2 concentration was not statistically different between groups. Administration of ASA prolonged the PFA-100 closure times, using Col + Epi (but not Col + ADP) as agonists. Furthermore, ASA resulted in a decrease in whole-blood platelet aggregation. Conclusions: Platelet function is influenced by breed, depending upon the methodology applied. However, the importance of these breed differences remains to be investigated. The PFA-100 method with Col + Epi as agonists, and ADP-induced platelet aggregation appear to be sensitive to ASA in dogs."

Canine Pancreatitis--From Clinical Suspicion to Diagnosis. Thomas Spillmann. 2008 WSAVA Congress. Quote: "Breeds with reported increased risk for chronic pancreatitis are cavalier King Charles and cocker spaniels, collies, and boxers."

Pancreatitis associated with clomipramine administration in a dog. P. H. Kook, A. Kranjc, M. Dennler, T. M. Glaus. J.Sm.Ani.Prac. 2009;50(1):95-98. Quote: "A three-year-old, male, entire, Yorkshire terrier was presented with peracute onset of abdominal pain and vomitus. Clinicopathological abnormalities included severely increased serum lipase activity, immeasurably high serum trypsin-like immunoreactivity and mild hypocalcaemia. Canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI) was intended to be measured, however, the sample got lost. Ultrasonography revealed a hypoechoic pancreas with small amounts of peripancreatic fluid and hyperechogenic mesentery. Acute pancreatitis (AP) was diagnosed and the dog recovered with appropriate therapy within 48 hours. Clomipramine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for alleviating signs of separation anxiety had been given for seven weeks. Two similar, albeit less severe, episodes associated with previous courses of clomipramine had occurred eight months earlier that responded to discontinuing clomipramine and supportive care. As SSRIs are associated with AP in human beings and no other trigger could be identified, we conclude that clomipramine should be considered as a potential cause when investigating causes for AP in susceptible breeds or other dogs presenting with compatible clinical signs."

Probiotics in veterinary practice. Susan G. Wynn. JAVMA March 2009;234(5):606-613. Quote: "Pancreatitis: Translocation of gastrointestinal bacteria during pancreatitis can lead to septicemia and substantially worsen a patient’s prognosis. Results of studies conducted in humans and other animals by use of Lactobacillus plantarum 299, Saccharomyces boulardii, and combinations of probiotics and prebiotics suggest that probiotic administration may be of benefit in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Probiotic organisms appear to improve the intestinal barrier, which prevents bacterial translocation, and lactic acid–producing bacteria can suppress the inflammation that makes systemic inflammation response syndrome such a deadly condition in patients with acute pancreatitis. Investigators have conducted studies in dogs with experimentally induced severe pancreatitis. Affected dogs have been provided nutrients parenterally as well as elemental enteral nutrition or dietary supplementation with probiotics. In 1 study, increases in serum activity of amylase, alanine aminotransferase, and aspartate aminotransferase and plasma concentrations of endotoxin, as well as pancreatic and ileal histopathologic changes, were significantly (P < 0.05) suppressed with probiotic administration. The degree of bacterial translocation was significantly (P < 0.05) decreased with probiotic administration, which suggested that this probiotic combination (described as 40 mg of Lactobacillus spp and 40 mg of Bifidobacterium spp) enhanced gastrointestinal barrier function. Investigators in another study obtained similar results."

Breed Predispositions to Disease in Dogs & Cats (2d Ed.). Alex Gough, Alison Thomas. 2010; Wiley-Blackwell Publ. 52.

Prevalence of hepatic lesions at post-mortem examination in dogs and association with pancreatitis. P. J. Watson, A. J. A. Roulois, T.J. Scase1, R. Irvine, M. E. Herrtage. J. Sm. An. Prac. Nov 2010;51(11):566–572. Quote: "To assess the prevalence of canine chronic hepatitis (CH) and other liver diseases in first opinion practice and identify associations with concurrent chronic pancreatitis (CP). ... The prevalence of CH was 12%. Some breeds had an increased RR of CH, although sample sizes were small. Dogs with CP had an increased RR of reactive hepatitis but no significant association with the other liver diseases. ... CH is common in the first opinion dog population but less common than CP. CP was significantly associated with reactive hepatitis but not CH. Possible breed associations mirrored another recent UK study. Some dogs with CP may be erroneously diagnosed clinically as having CH on the basis of increased serum liver enzymes because of concurrent reactive hepatitis if the diagnosis is not confirmed histologically."

Observational study of 14 cases of chronic pancreatitis in dogs. P. J. Watson, J. Archer, A. J. Roulois, T. J. Scase, M. E. Herrtage. Vet. Rec. Dec. 2010;167(25):968-976. Quote: "This study reports the clinical, clinicopathological and ultrasonographic findings from dogs with chronic pancreatitis (CP). Fourteen dogs with clinical signs consistent with CP and histological confirmation of the disease were evaluated. ... (...two Cavalier King Charles spaniels). ... Spaniels were the most common breed with CP, representing seven of the 14 dogs in this study. ... ...with Cavalier King Charles and cocker spaniels having a perilobular pattern, while other breeds had an intralobular distribution... There were a large number of spaniels in the current study, mirroring a pathology study (Watson and others 2007) that found an increased relative risk of pancreatitis in Cavalier King Charles and cocker spaniels, providing further evidence for breed-related disease in spaniels. ...CP was histologically severe in nine cases. Most dogs showed chronic low-grade gastrointestinal signs and abdominal pain. Five dogs had exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and five dogs had diabetes mellitus. The sensitivity of elevated trypsin-like immunoreactivity for CP was 17 per cent. The sensitivities of canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity, lipase and amylase for CP were 44 to 67 per cent or 14 to 28 per cent depending on the cut-off value used. Cholesterol was elevated in 58 per cent of samples. Liver enzymes were often elevated. The pancreas appeared abnormal on 56 per cent of ultrasound examinations. Ten dogs had died by the end of the study period; only one case was due to CP. CHRONIC pancreatitis (CP) in dogs is poorly documented clinically. However, a recent study reported the prevalence of CP to be 34 per cent in postmortem examinations of dogs from first opinion practice ... ."

Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency in Dogs. Joseph Cyrus Parambeth and Jörg M. Steiner. Consultant on Call: Gastroenterology, NAVC Clinician’s Brief ; May 2011. Quote: "Chronic pancreatitis can result in destruction of acinar cells (all breeds are affected, but cavalier King Charles spaniels and Jack Russell terriers may be predisposed)."

Genetic Connection: A Guide to Health Problems in Purebred Dogs, Second Edition. Lowell Ackerman. July 2011; AAHA Press; pg 76. Quote: "... breed predispositions have been reported for chow chows and Cavalier King Charles spaniels."

Sensitivity and Specificity of Canine Pancreas-Specific Lipase (cPL) and Other Markers for Pancreatitis in 70 Dogs with and without Histopathologic Evidence of Pancreatitis. S. Trivedi, S.L. Marks, P.H. Kass, J.A. Luff, S.M. Keller, E.G. Johnson, B. Murphy. J Vety Int Med Nov/Dec 2011;25(6):1241-1247. Quote: "Pancreatitis is a common disorder in dogs for which the antemortem diagnosis remains challenging. Objectives: To compare the sensitivity and specificity of serum markers for pancreatitis in dogs with histopathologic evidence of pancreatitis or lack thereof. Animals: Seventy dogs necropsied for a variety of reasons in which the pancreas was removed within 4 hours of euthanasia and serological markers were evaluated within 24 hours of death. Methods: Prospective study: Serum was analyzed for amylase and lipase activities, and concentrations of canine trypsin-like immunoreactivity (cTLI) and canine pancreas-specific lipase (cPL). Serial transverse sections of the pancreas were made every 2 cm throughout the entire pancreas and reviewed using a semiquantitative histopathologic grading scheme. Results: The sensitivity for the Spec cPL (cutoff value 400 μg/L) was 21 and 71% in dogs with mild (n = 56) or moderate-severe pancreatitis (n = 7), and 43 and 71% (cutoff value 200 μg/L), respectively. The sensitivity for the cTLI, serum amylase, and lipase in dogs with mild or moderate-severe pancreatitis was 30 and 29%; 7 and 14%; and 54 and 71%, respectively. The specificity for the Spec cPL based on 7 normal pancreata was 100 and 86% (cutoff value 400 and 200 μg/L, respectively), whereas the specificity for the cTLI, serum amylase, and lipase activity was 100, 100, and 43%, respectively. Conclusion and Clinical Importance: The Spec cPL demonstrated the best overall performance characteristics (sensitivity and specificity) compared to other serum markers for diagnosing histopathologic lesions of pancreatitis in dogs."