Urinary Tract Disorders in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels

-

Xanthinuria

Xanthinuria - • symptoms

- • diagnosis

- • DNA Testing

- • treatment

- Urinary Tract Infections

- Follicular Cystitis

- Organic Aciduria

- Urothelial Cell Carcinoma

- Research News

- Related Links

- Veterinary Resources

While urinary tract disorders caused by bacterial infections are common among all breeds of dogs, one such disorder, xanthinuria, is much more common in the cavalier King Charles spaniel. A much rarer, inflammatory disease of the bladder, follicular cystitis, has been reported in cavaliers more than in any other breed of dog.

Xanthinuria

Xanthine uroliths are crystals or sediment in the dog's urinary tract. The disorder, called xanthinuria or hyperxanthinuria, is the failure of xanthine, a natural product of the metabolism or purine*, to be dissolved by a process involving xanthine oxidase, and then secreted into the urine. Instead the xanthine concentrates into solids which remain in the urinary tract. The formation of crystals in the urinary tract is called urolithiasis.

*Purine is an organic compound which have many bodily functions, including serving as building blocks for DNA, aiding blood flow, oxygen delivery, inflammatory responses, and absorption of nutrients.

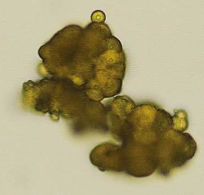

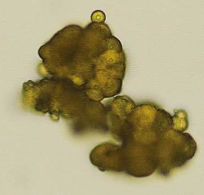

Urolithiasis is a relatively common problem in canines, but

the formation of naturally

occuring xanthine urolit crystals (see photo at left) is very rare. However, it has been found

often enough in related cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCS) to

conclude that it may be an hereditary defect in the breed, due to

an autosomal (non-sex-linked) recessive mode of inheritance. See this

November 1997 article and this

August 2011 article and this

May 2021 article.

Urolithiasis is a relatively common problem in canines, but

the formation of naturally

occuring xanthine urolit crystals (see photo at left) is very rare. However, it has been found

often enough in related cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCS) to

conclude that it may be an hereditary defect in the breed, due to

an autosomal (non-sex-linked) recessive mode of inheritance. See this

November 1997 article and this

August 2011 article and this

May 2021 article.

Cavaliers also are a notable exception in that they have been known to develop naturally occurring xanthine uroliths in their first year, while the average age of other breeds is five years. See this April 2010 article. Thus, in cavaliers, this disorder is considered to be congenital.

To the contrary however, in an August 2013 article involving 35 CKCSs, they concluded that "asymptomatic xanthinuria was not detected in this UK Cavalier King Charles spaniel population."

RETURN TO TOP

• Symptoms

Cavaliers affected with xanthinuria usually are asymptomatic. Observed symptoms include painful or difficult urination, very slow urination, and a continual or recurrent inclination to attempt to urinate. Also, in some cases, the urine may include some blood. Affected dogs may also display an abnormally great thirst.

RETURN TO TOP

• Diagnosis

In addition to the customary bodily examination and observation of

symptoms, diagnosis is determined by

blood and urine analyses,

x-ray (see light round object in x-ray at right), urinary

untrasounography, and retraction of the stones by urinary cathether and

repeated flushing, aspiration, and bladder agitation to retrieve the

stones for microscopic analysis. Urine typically would include

inflammatory urine sediment, including pyuria (white blood cells),

hematuria (red blood cells), and proteinuria (unusually high amounts of

protein).

blood and urine analyses,

x-ray (see light round object in x-ray at right), urinary

untrasounography, and retraction of the stones by urinary cathether and

repeated flushing, aspiration, and bladder agitation to retrieve the

stones for microscopic analysis. Urine typically would include

inflammatory urine sediment, including pyuria (white blood cells),

hematuria (red blood cells), and proteinuria (unusually high amounts of

protein).

In the August 2011 article, urolith analysis confirmed pure xanthine. Spot urine samples were submitted for purine analysis along with four controls. Uric acid was detected in all four controls but was not in the CKCS sample. Xanthine and hypoxanthine were detected in the CKCS sample but not in any controls.

RETURN TO TOP

• DNA

Testing

• DNA

Testing

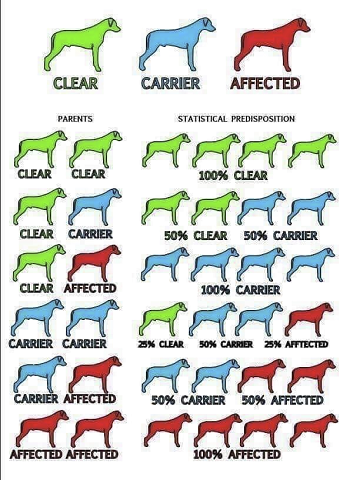

Research evidence indicates that xanthinuria may be an hereditary defect in the cavalier breed, due to an autosomal (non-sex-linked) recessive mode of inheritance.

In a

June 2016 abstract, the researchers reported finding that two

cavaliers had an homozygous mutation resulting in a premature

stop codon in molybdenum cofactor sulfurase (MOCOS, type 2 xanthinuria). Mutation-specific assays were

developed to genotype 108 CKCSs without a history of urolithiasis. Of

the 108 cavaliers, 105 were clear, three were carriers, and none were

homozygous for the CKCS

mutation. They concluded that:

mutation. They concluded that:

"[D]iverse mutations underlie canine hereditary xanthinuria. Genetic testing can help inform breeders and identify dogs that may benefit from preventative therapies. Future studies are needed to determine mutation frequencies in other breeds and whether clinical outcome differs between the mutations."

In a September 2021 article, a team of University of Minnesota veterinary researchers sought to determine the molecular basis of hereditary xanthinuria in three cavalier King Charles spaniels and five dogs of three other breeds ((Manchester Terrier, English cocker spaniel, and dachshund). They report finding ten possible variants causing the disorder. they also report that North American cavaliers appear to have a lower variant frequency than CKCSs in the United Kingdom and elsewhere. Overall, they conclude that there appear that multiple diverse variants responsible for hereditary xanthinuria in dogs, and that the results suggest that affected amino acids may have a critical role in enzyme function.

Genetic testing laboratories which test for this mutation causing xanthinuria include:

• Canine Genetics Lab, University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine

• Embark, Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

• Laboklin

• MyDogDNA, Wisdom Panel

![]() Watch

this YouTube video to learn how to properly use a swab to obtain DNA from

your dog. See our Genetic Testing webpage for

more information about DNA testing.

Watch

this YouTube video to learn how to properly use a swab to obtain DNA from

your dog. See our Genetic Testing webpage for

more information about DNA testing.

RETURN TO TOP

• Treatment

The

American Society of

Veterinary Nephrology and Urology (ASVNU) maintains a list of urology

specialists in the United States and internationally, which is

linked here.

In April 2022, the American College of

Veterinary Nephrology and Urology (ACVNU), a specialty

college providing advanced training and board certification in

veterinary kidney and urinary medicine, was established. All of its

residents are boarded specialists in another veterinary discipline. Thus

far, the ACVNU has not published a list of boarded members.

The

American Society of

Veterinary Nephrology and Urology (ASVNU) maintains a list of urology

specialists in the United States and internationally, which is

linked here.

In April 2022, the American College of

Veterinary Nephrology and Urology (ACVNU), a specialty

college providing advanced training and board certification in

veterinary kidney and urinary medicine, was established. All of its

residents are boarded specialists in another veterinary discipline. Thus

far, the ACVNU has not published a list of boarded members.

The usual treatment for dogs with xanthinuria is to flush the crystals from the body with fluids and to feed them a low-protein alkalizing diet. Eggs, nuts, and dairy products are generally low purine sources of protein. Foods with high purine content (to be avoided) are liver, bacon, kidney, and most seafoods. Canned foods are advised, due in part to their moisture content. Additional water may be added to the meals. If flushing is not successful, surgical removal of the stones is necessary.

Allopurinol (Zyloprim) is a drug used to treat dogs suffering from urate bladder stones and from leishmaniasis, a parasite common in certain localities. Allopurinol is an inhibitor of xanthine oxidase, which means that it unfortunately tends to enable the creation of xanthine crystals. See this July 2015 article. In a June 2016 article, researchers studied 320 dogs while receiving allopurinol treatment for leishmaniasis. They found that 29 of the dogs developed xanthinuria and related urinary conditions. Of those dogs, 19 displayed urinary clinical signs. This has been described as "acquired xanthinuria", to distinguish it from the naturally occuring form of xanthinuria in cavaliers. Therefore, care should be taken to not prescribe allopurinol to cavaliers either to treat them for xanthinuria or for leishmaniasis.

A team of ACVIM small animal specialists have issued an ACVIM Consensus Statement on recommendations for treating and preventing uroliths in dogs (and cats), in a September 2016 article. Regarding xanthinuria (xanthine oxidase), they focus on administering allopurinol resulting in the formation of xanthine uroliths. They explain that it "occurs because allopurinol inhibits the metabolism of xanthine to uric acid and because xanthine is less soluble in urine than is uric acid." They therefore recommend a lower dosage of allopurinol "to safely prevent urate uroliths."

That 2016 Consensus Statement also recommends that the affected dog be fed a high moisture food, and not a high-sodium dry food. It recommends limiting sodium intake, and limiting animal protein intake.

In a November 2018 article, Japanese veterinary researchers report finding that when watermelon extract beverage was substituted for water for 12 dogs for 3 months, the dogs' serum leptin levels were reduced and inhibited the formation of urine crystals such as calcium oxalate and struvite crystals.

RETURN TO TOP

Urinary Tract Infections

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are common among all breeds of dogs. Roughly 14% will develop at least one case of UTI in their lifetimes. Typical symptoms of UTIs include an urgency to urinate, blood in urine, and pain, especially during urination.

The usual cause is bacteria which enter the dog's urethra and spread in the bladder. Tests of the urine are the usual means of diagnosis. Common bacteria include Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. Because UTIs can be very painful, and urinalysis takes time due to the necessity of testing cultures, the customary immediate treatment is an oral antimicrobial, such as amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (14-19 mg/kg PO q12h), pending the results of urinalysis. The antimicrobial may be changed if the bacteria found is known to be resistant to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Other antimicrobials include ofloxacin, cephalexin, and nitrofurantoin. The bacteria causing UTIs have been found to develop resistance to some antibiotics, resulting in the failure of the treatment.

In a September 2024 article, veterinary urologists studied the curative effects of a strain of Escherichia coli (asymptomatic bacteriuria E. coli 212) upon dogs diagnosed with urinary tract infections (UTIs) and compared to the curative effects of conventional antimicrobial treatments. Of 32 dogs in the study, 5 were cavaliers (15.6%), the highest percentage among the breeds involved. E. coli ASB 212 is a biotherapeutic. It is mixed with saline and inserted into the sedated dog's bladder using a urinary catheter. They report finding that:

"The biotherapeutic, ASB E. coli 212, was not inferior to antimicrobial treatment when evaluating clinical cure for dogs with recurrent UTI in this 2-week clinical trial. Furthermore, longer term outcomes demonstrated promising results in some dogs, whereby clinical cure was documented for as long as 13 months. No dogs experienced any major adverse events."

RETURN TO TOP

Follicular Cystitis

Follicular cystitis is a rare, inflammatory disease of the bladder which primarily affects females. In a report in August 2014 the first case of follicular cystitis in a dog, a female cavalier King Charles spaniel, was reported. Cystitis is inflammation of the bladder. Most cases of the inflammation are caused by a bacterial infection, and they are called a urinary tract infection (UTI). Follicular cystitis is characterized by the presence of lymphoid follicles with germinal center formation. See also this September 2015 article.

RETURN TO TOP

Organic Aciduria

The term "organic aciduria" describes the accumulation of one or more carboxylic acids in the tissues of the urinary tract and urine itself. In the case of one cavalier in this May 2007 article, the dog had excessive urinary levels of hexanoylglycine, attributed to a deficiency of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. The consequence of organic aciduria frequently is seizure activity, including intermittent head tremors, episodes of ataxia (voluntary muscular movements) and hypermetria of the front legs (movement of them beyond the dog's intented movement), a stupor, excessive blinking and facial twitching, and involuntary jaw movements, lasting up to 10 seconds per episode and up to 50 times a day. The treating veterinarians found that potassium bromide, phenobarbital, and levetiracetam were effective in controlling the seizure activity. However, the cavalier eventually had several episodes of "status epilepticus" (a seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more seizures within a five-minute period without the dog returning to normal between them) and was euthanized. See our webpage on "Medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD) in the cavalier King Charles spaniel" for more information.

RETURN TO TOP

Urothelial Cell Carcinoma

Urothelial cell carcinoma (UCC) is a cancer of the bladder which is common among humans and dogs. While it has been found in UK studies to be most prevalent in Scottish terriers, Shetland sheepdogs, and West Highland white terriers, it has been detected in cavaliers as well. See this May 2018 article.

In this February 2024 article, not including any CKCSs, USA researchers report finding that:

"In this case–control study, we found that swimming in a pool was a significant risk factor for UCC in dogs. Chlorinated water can contain reactive breakdown products (trihalomethanes, especially bromoform) that are mutagenic. Chlorination byproducts have been linked to UCC in people, especially through swimming, bathing, and showering."

RETURN TO TOP

Research News

September 2024:

E. coli inserted into cavaliers' and other dogs'

bladders cured urinary tract infections.

In a

September 2024 article, a team of veterinary urologists

(Gilad Segev, Hilla Chen, Jonathan D. Dear, Beatriz Martínez López,

Jully Pires, David J. Klumpp, Anthony J. Schaeffer, Jodi L. Westropp

[right]) studied the curative effects of a strain of

Escherichia coli (asymptomatic bacteriuria E. coli 212) upon dogs

diagnosed with urinary tract infections (UTIs) and compared to the

curative effects of conventional antimicrobial treatments. Of 32

dogs in the study, 5 were cavalier King Charles spaniels (15.6%),

the highest percentage among the breeds involved. E. coli ASB 212 is

a biotherapeutic. It is mixed with saline and inserted into the

sedated dog's bladder using a urinary catheter. They report finding

that:

In a

September 2024 article, a team of veterinary urologists

(Gilad Segev, Hilla Chen, Jonathan D. Dear, Beatriz Martínez López,

Jully Pires, David J. Klumpp, Anthony J. Schaeffer, Jodi L. Westropp

[right]) studied the curative effects of a strain of

Escherichia coli (asymptomatic bacteriuria E. coli 212) upon dogs

diagnosed with urinary tract infections (UTIs) and compared to the

curative effects of conventional antimicrobial treatments. Of 32

dogs in the study, 5 were cavalier King Charles spaniels (15.6%),

the highest percentage among the breeds involved. E. coli ASB 212 is

a biotherapeutic. It is mixed with saline and inserted into the

sedated dog's bladder using a urinary catheter. They report finding

that:

"The biotherapeutic, ASB E. coli 212, was not inferior to antimicrobial treatment when evaluating clinical cure for dogs with recurrent UTI in this 2-week clinical trial. Furthermore, longer term outcomes demonstrated promising results in some dogs, whereby clinical cure was documented for as long as 13 months. No dogs experienced any major adverse events."

September 2021:

Diverse molecular bases for hereditary xanthine urolithiasis in

cavaliers are located in a University of Minnesota study.

In

a

September 2021 article, a team of University of Minnesota veterinary

researchers (Nicole M. Tate [right], Katie M. Minor, Jody P.

Lulich, James R. Mickelson, Allyson Berent, Jonathan D. Foster, Kasey H.

Petersen, Eva Furrow) sought to determine the molecular basis of

hereditary xanthinuria in three cavalier King Charles spaniels and five

dogs of three other breeds ((Manchester Terrier, English cocker spaniel,

and dachshund). They report finding ten possible variants causing the

disorder. they also report that North American cavaliers appear to have

a lower variant frequency than CKCSs in the United Kingdom and

elsewhere. Overall, they conclude that there appear that multiple

diverse variants responsible for hereditary xanthinuria in dogs, and

that the results suggest that affected amino acids may have a critical

role in enzyme function.

In

a

September 2021 article, a team of University of Minnesota veterinary

researchers (Nicole M. Tate [right], Katie M. Minor, Jody P.

Lulich, James R. Mickelson, Allyson Berent, Jonathan D. Foster, Kasey H.

Petersen, Eva Furrow) sought to determine the molecular basis of

hereditary xanthinuria in three cavalier King Charles spaniels and five

dogs of three other breeds ((Manchester Terrier, English cocker spaniel,

and dachshund). They report finding ten possible variants causing the

disorder. they also report that North American cavaliers appear to have

a lower variant frequency than CKCSs in the United Kingdom and

elsewhere. Overall, they conclude that there appear that multiple

diverse variants responsible for hereditary xanthinuria in dogs, and

that the results suggest that affected amino acids may have a critical

role in enzyme function.

May 2021:

Cavaliers and dalmatians were the most common breeds diagnosed

with xanthine uroliths in UC-Davis study of 10,444 dogs.

In

a

May 2021 article, Univeristy of California at Davis researchers

(Lucy Kopecny, Carrie A. Palm, Gilad Segev, Jodi L. Westropp [right])

reviewed the medical records of 10,444 cases of uroliths in dogs between

2006 and 2018. Among the types of urinary crystals observed, 25 dogs

were found to have xanthine in their crystals, including three (12.0%)

cavalier King Charles spaniels. Overall, calcium oxalate‐ and

struvite‐containing uroliths were the most common urolith crystals

obtained from the 10,444 patients.

In

a

May 2021 article, Univeristy of California at Davis researchers

(Lucy Kopecny, Carrie A. Palm, Gilad Segev, Jodi L. Westropp [right])

reviewed the medical records of 10,444 cases of uroliths in dogs between

2006 and 2018. Among the types of urinary crystals observed, 25 dogs

were found to have xanthine in their crystals, including three (12.0%)

cavalier King Charles spaniels. Overall, calcium oxalate‐ and

struvite‐containing uroliths were the most common urolith crystals

obtained from the 10,444 patients.

August 2020:

UK vets find association between bacteria in urine and

neurological deficits in two cavaliers.

In an

August 2020 article, a pair of UK veterinary neurologists (Abbe H.

Crawford [right], Thomas J. A. Cardy) at the

Royal Veterinary College reviewed the cases of seven dogs, including two

cavalier King Charles spaniels (28.5%), and four cats, all of which had

been diagnosed with bacteriuria (bacteria in the urine) and neurological

deficits which improved or resolved after starting treatment for the

bacteria. In general, they concluded by recommending that:

In an

August 2020 article, a pair of UK veterinary neurologists (Abbe H.

Crawford [right], Thomas J. A. Cardy) at the

Royal Veterinary College reviewed the cases of seven dogs, including two

cavalier King Charles spaniels (28.5%), and four cats, all of which had

been diagnosed with bacteriuria (bacteria in the urine) and neurological

deficits which improved or resolved after starting treatment for the

bacteria. In general, they concluded by recommending that:

"Urinalysis, including bacteriological culture and sensitivity, should be performed in patients presenting with an acute onset of neurological deficits (particularly deficits consistent with a diffuse forebrain localisation), even in the absence of clinical signs of lower urinary tract inflammation."

Specifically regarding the two cavaliers, here are the details of their cases:

• Case 5: 11.5 year old female neutered CKCS; symptoms: acute onset of abnormal episodes consisting of head nodding, tremors, swaying and collapse lasting a few seconds, and occurring approximately 15 times per day; urine culture: Staph pseudointermedius; MRI of head: normal; treatment: 14 days of amoxicillin clauvulanate, then 14 days of levetiracetam; outcome: resolution of obtundation with treatment, neurologically normal at follow up 4 months later).

• Case 6: 5.5 year old male neutered CKCS; symptoms: Acute onset of disorientation, progressive obtundation, inappetance, five focal seizures in the 12 hours prior to referral (Last seizure 5 hours prior to presentation); urine culture: E. coli; MRI of head: mild ventriculomegaly and Chiari-like malformation; treatment: 14 days amoxicillin clavulanate; outcome: Gradual improvement in mentation after initiation of treatment, resolution of pollakiuria and dysuria within 48 hrs., negative urine culture 14 days after discharge, no further focal seizures and neurologically normal at time of follow up 3 months later.

November 2018: Watermelon extract found to inhibit formation of urine crystals in dogs. In a November 2018 article, Japanese veterinary researchers (Sayaka Miyai, Toshiharu Hashizume, Toshio Okazaki) report finding that when watermelon extract beverage was substituted for water for 12 dogs for 3 months, the dogs' serum leptin levels were reduced and inhibited the formation of urine crystals such as calcium oxalate and struvite crystals.

August 2017:

University of Minnesota's Canine Genetics Laboratory offers a

genetic test for CKCS xanthinuria.

The

Canine Genetics Laboratory at the University of Minnesota's veterinary school

offers an inexpensive genetic test to determine if dogs have the

CKCS mutation (or either of two others) causing hereditary xanthinuria.

This would be a simple means of confirming whether cavalier breeding

stock has the mutation, if the blood line has a history of crystals or

sediment in the dogs' urinary tracts.

The

Canine Genetics Laboratory at the University of Minnesota's veterinary school

offers an inexpensive genetic test to determine if dogs have the

CKCS mutation (or either of two others) causing hereditary xanthinuria.

This would be a simple means of confirming whether cavalier breeding

stock has the mutation, if the blood line has a history of crystals or

sediment in the dogs' urinary tracts.

September 2016: ACVIM

issues "Consensus Recommendations on the Treatment and Prevention of

Uroliths in Dogs".

A team of ACVIM small animal specialists

(Jody P. Lulich [right], A.C. Berent, L.G. Adams, J.L. Westropp, J.W. Bartges, C.A.

Osborne) have issued an ACVIM Consensus Statement on recommnedations for

treating and preventing uroliths in dogs (and cats), in a

September 2016 article. Regarding xanthinuria (xanthine oxidase),

they focus on administering allopurinol resulting in the formation of

xanthine uroliths. They explain that it "occurs because allopurinol

inhibits the metabolism of xanthine to uric acid and because xanthine is

less soluble in urine than is uric acid." They therefore recommend a

lower dosage of allopurinol "to safely prevent urate uroliths."

A team of ACVIM small animal specialists

(Jody P. Lulich [right], A.C. Berent, L.G. Adams, J.L. Westropp, J.W. Bartges, C.A.

Osborne) have issued an ACVIM Consensus Statement on recommnedations for

treating and preventing uroliths in dogs (and cats), in a

September 2016 article. Regarding xanthinuria (xanthine oxidase),

they focus on administering allopurinol resulting in the formation of

xanthine uroliths. They explain that it "occurs because allopurinol

inhibits the metabolism of xanthine to uric acid and because xanthine is

less soluble in urine than is uric acid." They therefore recommend a

lower dosage of allopurinol "to safely prevent urate uroliths."

June 2016: University of Minnesota researchers locate a DNA mutation causing hereditary xanthinuria in cavaliers. In a June 2016 abstract, University of Minnesota researchers (Eva Furrow, Nicole Tate, Katie Minor, James Mickelson, Kasey Peterson, Jody Lulich) reported finding that two cavaliers had an homozygous mutation xaresulting in a premature stop codon in molybdenum cofactor sulfurase (MOCOS). Mutation-specific assays were developed to genotype 108 CKCSs without a history of urolithiasis. Of the 108 cavaliers, 105 were clear, three were carriers, and none were homozygous for the CKCS mutation. They concluded that:

"[D]iverse mutations underlie canine hereditary xanthinuria. Genetic testing can help inform breeders and identify dogs that may benefit from preventative therapies. Future studies are needed to determine mutation frequencies in other breeds and whether clinical outcome differs between the mutations."

June 2016: Allopurinol causes xanthinuria in dogs treated for leishmaniasis. In a June 2016 article, Spanish researchers (M. Torres, J. Pastor, X. Roura, M. D. Tabar, Espada, A. Font, J. Balasch, M. Planellas) studied 320 dogs treated with allopurinol for canine leishmaniasis. Forty-two of the 320 dogs -- 13% -- developed xanthinuria.

June 2015:

Researchers emphasize importance of differentiating urine crystals in

cavaliers.

In a

June 2015

study, North Carolina State veterinary school researchers (Kaori

Uchiumi Davis, Carol B. Grindem) reported the importance in determining

the type of urine sediments, particularly in cavalier King Charles

spaniels. In this case, the patient was a male castrated Dalmatian with

a stone and sediment in his urine. The crystals (right) did not dissolve in

acetic acid or hydrochloric acid, but did dissolve in 1 N sodium

hydroxide, ruling out ammonium biurates. Using infrared spectroscopy,

the researchers determined that the spectrum of crystals most closely

matched xanthine. The dog had been treated with allopurinol, which is

used to treat dogs with uric acid crystals. However, allopurinol binds

to and inhibits the action of xanthine oxidase, thereby decreasing

conversion of xanthine to uric acid. Xanthine has low urine solubility,

and therefore xanthinuria may trigger xanthine crystalluria or

urolithiasis. In cavaliers, xanthinuria is hereditary. Since the

solubility results in this case suggest that xanthine crystals may be

significantly different than urate crystals, it therefore is important to

differentiate these crystals before treatment.

In a

June 2015

study, North Carolina State veterinary school researchers (Kaori

Uchiumi Davis, Carol B. Grindem) reported the importance in determining

the type of urine sediments, particularly in cavalier King Charles

spaniels. In this case, the patient was a male castrated Dalmatian with

a stone and sediment in his urine. The crystals (right) did not dissolve in

acetic acid or hydrochloric acid, but did dissolve in 1 N sodium

hydroxide, ruling out ammonium biurates. Using infrared spectroscopy,

the researchers determined that the spectrum of crystals most closely

matched xanthine. The dog had been treated with allopurinol, which is

used to treat dogs with uric acid crystals. However, allopurinol binds

to and inhibits the action of xanthine oxidase, thereby decreasing

conversion of xanthine to uric acid. Xanthine has low urine solubility,

and therefore xanthinuria may trigger xanthine crystalluria or

urolithiasis. In cavaliers, xanthinuria is hereditary. Since the

solubility results in this case suggest that xanthine crystals may be

significantly different than urate crystals, it therefore is important to

differentiate these crystals before treatment.

August 2014: UK vets find follicular cystititis in a cavalier. A team of veterinarians at the University of Glasgow in the UK report in August 2014 the first case of follicular cystitis in a dog, a female cavalier King Charles spaniel. Cystitis is inflammation of the bladder. Most cases of the inflammation are caused by a bacterial infection, and they are called a urinary tract infection (UTI). Follicular cystitis is characterized by the presence of lymphoid follicles with germinal center formation.

RETURN TO TOP

Related Links

RETURN TO TOP

Veterinary Resources

Xanthine-containing urinary calculi in dogs given allopurinol. Ling GV, Ruby AL, Harrold DR, Johnson DL. JAVMA. 1991;198(11):1935-1940. Quote: Clinical features and laboratory findings were evaluated in 10 dogs that formed xanthine-containing urinary calculi during the period that they were given allopurinol (9 to 38 mg/kg of body weight/d). Duration of allopurinol treatment was 5 weeks to 6 years. Of the 10 dogs, 9 (all Dalmatians) had formed uric acid-containing calculi at least once before allopurinol treatment was initiated. It was not possible to recognize xanthine as a crystalline component of the calculi by use of a chemical colorimetric method or by polarized light microscopy. We concluded that the best diagnostic method for recognition of xanthine-containing calculi was high-pressure liquid chromatography because it is quantitative, sensitive, and accurate, and can be conducted on a small amount (1 to 2 mg) of crystalline material.

Xanthinuria (xanthine oxidase deficiency) in two cavalier king charles spaniels. C.D. van Zuilen , R.F. Nickel, D‐J. Reijngoud. Vet. Qtrly. April 1996;18:sup1-24-25. Quote: A 7-month-old male Cavalier King Charles spaniel was referred to the Department of Clinical Sciences of Companion Animals, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, because signs of dysuria and stranguria. ... One littermate and the control dog had normal concentrations of hypoxanthine and xanthine in the urine. The patient and the other littermate had high levels of hypoxanthine and xanthine in the urine (HPLC method and identification witILUV absorption spectrum). Xanthinuria is a well-known but rare hereditary disorder in man (2), characterized by a gross deficiency of the enzyme xanthine oxidase. This enzyme catalyzes the conversion of hypoxanthine to xanthine and of xanthine to uric acid, the end product of purine metabolism in man and higher primates. ... Only two cases of naturally-occurring xanthine calculi in dogs have been reported. One concerned renal calculi in a King Charles spanieland the other concerned urethral uroliths in a Cavalier King Charles spaniel. Neither dog had received any allopurinol medication. Allopurinol is an inhibitor of xanthine oxidase and administration of excessive doses of this drug can cause hyperxanthinuna and formation of xanthine calculi. Neither of the Cavalier King Charles spaniels in this report had received any allopurinol medication. The fact that two littermates were shown to have xanthine oxidase deficiency suggests the possibility of a hereditary xanthine oxidase deficiency in Cavalier King Charles spaniels. (See. also, the November 1997 article below.)

Xanthinuria in a family of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels.

C.D. van Zuilen, R.F. Nickel, T.H. van Dijk, D‐J. Reijngoud.

Vet.Quarterly. November 1997;19:172-174. Quote: "Xanthine calculi were

found in a 7-month-old male Cavalier King Charles spaniel

with urethral obstruction and renal insufficiency. Because the only two

other reported cases of naturally occurring xanthine urolithiasis

concerned a Cavalier King Charles and a King Charles

spaniel the urine of the littermates and parents of the patient were

also examined for xanthinuria. Semi-quantitative analysis revealed high

urine concentrations of hypoxanthine and xanthine in the patient and his

female littermate. Quantitative analysis by high-pressure liquid

chromatography (HPLC) of the urine samples from the family of this

Cavalier King Charles spaniel and nine control dogs

revealed that hypoxanthine and xanthine excretion was 30 and 60 times

higher in the affected patient and the female littermate than in the

others dogs. The pattern of xanthinuria, which is caused by a deficiency

of the enzyme xanthine oxidase, in the relation diagram of this family

of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels was consistent with

an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. (See, also, the

April 1996 article above.)

C.D. van Zuilen, R.F. Nickel, T.H. van Dijk, D‐J. Reijngoud.

Vet.Quarterly. November 1997;19:172-174. Quote: "Xanthine calculi were

found in a 7-month-old male Cavalier King Charles spaniel

with urethral obstruction and renal insufficiency. Because the only two

other reported cases of naturally occurring xanthine urolithiasis

concerned a Cavalier King Charles and a King Charles

spaniel the urine of the littermates and parents of the patient were

also examined for xanthinuria. Semi-quantitative analysis revealed high

urine concentrations of hypoxanthine and xanthine in the patient and his

female littermate. Quantitative analysis by high-pressure liquid

chromatography (HPLC) of the urine samples from the family of this

Cavalier King Charles spaniel and nine control dogs

revealed that hypoxanthine and xanthine excretion was 30 and 60 times

higher in the affected patient and the female littermate than in the

others dogs. The pattern of xanthinuria, which is caused by a deficiency

of the enzyme xanthine oxidase, in the relation diagram of this family

of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels was consistent with

an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. (See, also, the

April 1996 article above.)

Refractory Seizures Associated With an Organic Aciduria in a Dog. Simon Platt, Yvonne L. McGrotty, Carley J. Abramson, Cornelis Jakobs. J. Amer. Anim. Hosp. Assn. May 2007;43(3):163-167. Quote: The purpose of this report is to describe a new organic aciduria in a dog (i.e., hexanoylglycinuria potentially from medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency) and treatment of the associated seizures with levetiracetam. ... A 6-month-old, female Cavalier King Charles spaniel exhibited seizures that were difficult to control with standard anticonvulsants over a 12-month period. The diagnosis of an organic aciduria with excessive excretion of hexanoylglycine was determined when the dog was 20 months old. Recurrent and cluster seizures were eventually controlled with the addition of levetiracetam to potassium bromide and phenobarbital.

Canine Purine Urolithiasis - Causes, Detection, Management and Prevention. Carl A. Osborne, Joseph W. Bartges, Jody P. Lulich, Hasan Albasan, Carroll Weiss. Chapter 39 in Small Animal Clinical Nutrition, 5th ed. May 2010. Quote: Naturally occurring xanthinuria and xanthine urolithiasis have been reported to occur in a few dogs (Kidder and Chivers, 1968; Kucera et al, 1997). Xanthine urolithiasis was reported in a family of cavalier King Charles spaniels (van Zuilen et al, 1997). ... At the Minnesota Urolith Center, the mean age of dogs at the time of xanthine urolith retrieval was five years (range = three to 168 months). In this regard, the cavalier King Charles spaniel breed is an exception inasmuch that naturally occurring xanthine uroliths have been recognized when these dogs were less than one year of age.

Xanthine urolithiasis in a Cavalier King Charles spaniel. Gow, A.G., Fairbanks, L.D., Simpson, J.W., Jacinto, A.M., Ridyard, A.E. Vet. Rec. August 2011;169:209. Quote: "This case is a CKCS in the UK with xanthine urolithiasis and urine purine concentrations after medical management. A four-year old entire male CKCS was referred to the R(D)SVS with a history of polydipsia and intermittent strangury. ... Spot urine samples were submitted for purine analysis along with four controls. Uric acid was detected in all controls but was not in the CKCS sample. Xanthine and hypoxanthine were detected in the CKCS sample but not in any controls. This was suggestive of a defect in purine metabolism, likely a xanthine dehydrogenase deficiency. ... Primary xanthinuria reported in the CKCS is thought to be a genetic defect inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, as in humans). The defect may be a type I or II XDH deficiency. Administration of allopurinol and metabolite analysis would differentiate these; however as this would not alter management, and also have required a control population, this was not performed. XDH activity may also be measured in hepatic or intestinal tissue), this was also not ethically justified. ... Xanthine deposition is thought to cause calculogenic pyelonephritis. This case presented with signs of renal failure which is consistent with the four other symptomatic cases reported. ... In this case, the diet fed was alkalinizing and the urinary pH was 7, the recommended pH for human urine in primary xanthinuria management. In vitro studies and clinical cases have shown minimal dissolution at physiological pH levels therefore at best this is a preventative measure. Although urine specific gravity reduced subsequent to initial presentation, it is unknown whether this was due to improved oral water intake or a deterioration of renal function and poor concentrating ability. In humans, xanthine concentrations below 3 mmol/l are suggested to reduce urolith formation. This was not consistently achieved and uroliths recurred. Urinary xanthine excretion normalised to creatinine appeared to increase compared to the first measurement. This may have been due to poor dietary compliance."

Urine Concentrations of Purine Metabolites in UK Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. .M.L. Jacinto, R.J. Mellanby, M.L. Chandler, N.X. Bommer, H. Carruthers, L.D. Fairbanks, A. Gow. J.Vet.Intern.Med. Nov. 2012; 26(6):1505–1538. Quote: “Xanthine urolithiasis is a rare condition accounting for 0.1% of all canine urolithiasis in one study. This pathology has been reported as a primary disorder in dogs, most notably in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS). Xanthine is an intermediate product of purine metabolism, which is converted from hypoxanthine by xanthine oxidase. Xanthine is only slightly soluble in urine and therefore hyperxanthinuria may lead to urolith formation. It has been speculated that some CKCS have an inherited mutation in the xanthine oxidase gene. In humans, isolated deficiency of xanthine oxidase occurs rarely and approximately 50% of individuals are asymptomatic, despite having significant xanthinuria. Therefore we hypothesised that asymptomatic xanthinuria may be commonplace in the UK population of CKCS. In support of this, a previous case report of a symptomatic CKCS reported significant xanthinuria occurring in an asymptomatic sibling. In order to examine the prevalence of xanthinuria in CKCS, urine concentrations of hypoxanthine and xanthine metabolites as well as creatinine were measured in 35 client-owned Cavalier King Charles Spaniel dogs and 24 dogs of other breeds from three first-opinion veterinary practices in the UK. Urine samples were collected by free catch and purine metabolites were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography. Ratios of xanthine/creatinine and hypoxanthine/creatinine from the two populations were compared by Mann Whitney U test and were found not to be significantly different (p=0.41 and p=0.59 respectively). In the control population, the xanthine/creatinine ratio ranged from 0.00018 to 0.01611 (median 0.00069), while in the CKCS population it ranged from 0.000154 to 0.005794 (median 0.000435). These results are markedly lower than the previously reported case of xanthine urolithiasis in a UK CKCS dog, which utilised the same reference laboratory (xanthine/creatinine ratio 0.406). These data suggest that asymptomatic xanthinuria is not prevalent in the UK CKCS population.”

Urine concentrations of xanthine, hypoxanthine and uric acid in UK Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Ana Margarida Leça Jacinto, Marjorie Chandler, Nick X. Bommer, Harvey Carruthers, Lynette D. Fairbanks, Richard J. Mellanby, Adam G. Gow. J. Small Anim. Pract. August 2013;54(8):395-398. Quote: "Objectives: Xanthine urolithiasis and asymptomatic xanthinuria have been diagnosed in Cavalier King Charles spaniel dogs suggesting that primary xanthinuria may be a breed-related disorder, although its prevalence remains unclear. The hypothesis of this study was that asymptomatic xanthinuria is common in Cavalier King Charles spaniel dogs. Methods: Free catch urine samples were collected from 35 client-owned Cavalier King Charles spaniel dogs and from 24 dogs of other breeds. The purine metabolites were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography. The urine ratios of xanthine/ creatinine and hypoxanthine/creatinine were calculated and compared between the two groups of dogs. Results: The urine concentrations of purine metabolites were not significantly different between the two groups and were very low in both. The urine concentrations of xanthine in all 35 Cavalier King Charles spaniel were markedly lower than in the previously reported case of xanthine urolithiasis in a UK Cavalier King Charles spaniel dog. Clinical Significance: Asymptomatic xanthinuria was not detected in this UK Cavalier King Charles spaniel population. This data may be used as a reference for urinary purine metabolite concentrations in the dog."

Follicular cystitis in a dog. Rui Moncao Sul, Gawain Hammond, Kathryn Pratschke. Vet.Rec. Case Report. August 2014;2(1). Quote: A four-year-old female Cavalier King Charles Spaniel with a history of recurrent lower urinary tract disease refractory to treatment was referred to our hospital. Clinical examination was unremarkable apart from thickening of the dorsal vulva. Abdominal ultrasound was compatible with possible areas of mild thickening of the bladder wall. Lower genitourinary-contrast radiographic studies showed multiple small lesions in the bladder wall. Surgical biopsy of the bladder was compatible with follicular cystitis and excised uterine tissue was consistent with cervicitis. Clinical signs resolved after treatment with a combination of antibiosis, NSAIDs, pentosan polysulfate and amitriptyline. Follow-up 30 months after surgery confirmed that the dog was free of clinical signs. Follicular cystitis has not been previously reported in dogs but should be considered as a differential for patients with refractory long-standing lower urinary tract disease.

What is your diagnosis? Urine crystals from a dog. Kaori Uchiumi Davis, Carol B. Grindem. Vet. Clinical Pathology. June 2015;44(2):331–332. Quote: "A 5-year-old male castrated Dalmatian weighing 19.5 kg was evaluated by the referring veterinarian for being unable to urinate. A lateral radiograph showed potential mineralized material in the ureters. The dog was administered buprenorphine [Temgesic sublingual] and acepromazine ... Additional radiographs were taken at North Carolina State University Veterinary Health Complex (NCSU-VHC) which did not reveal a radiopaque stone. Urinary catheterization was performed and a stone was found in the urethra and flushed into the bladder. The dog was prescribed allopurinol 300 mg BID and the stranguria resolved. The dog was reevaluated 2 months later. A urinalysis with sediment examination was performed and revealed mild alkalinuria (pH 9.0; reference interval 4.5–8.5). Urine was opaque golden colored with a specific gravity of 1.023, pH of 9, trace protein, negative glucose, trace ketone, and 1 + bilirubin. A sulfosalicylic acid protein precipitation test was trace positive. Examination of sediment revealed rare epithelial cells, many fat droplets, and many yellow-brown small spherules of ammonium biurate-like crystals. The crystals did not dissolve in acetic acid or hydrochloric acid, but did dissolve in 1 N sodium hydroxide, ruling out ammonium biurates. The spectrum of crystals determined by infrared spectroscopy most closely matched xanthine. Xanthine is a product of purine metabolism and is converted to uric acid by the enzyme xanthine oxidase. Xanthine crystals are impossible to distinguish from ammonium biurate or amorphous urates by light microscopy. All of these crystals have yellow-brown color and appear globular to amorphous. Infrared spectroscopy or high-pressure liquid chromatography can be used to confirm xanthine crystalluria. Xanthine crystalluria and urolithiasis are rare in small animals; uroliths with at least 70% xanthine were reported to account for less than 0.1% of all canine uroliths. It usually occurs secondary to therapy with allopurinol. Xanthinuria associated with allopurinol therapy is influenced by several variables including the dosage of allopurinol, quantity of dietary purine precursors, the rate of degradation, and hepatic function. Allopurinol is used to treat dogs with uric acid crystals. It is also used to treat infectious diseases such as leishmaniasis and trypanosomiasis, as it is incorporated into RNA, leading to blockage of de novo synthesis of purine nucleotides. It binds to and inhibits the action of xanthine oxidase, thereby decreasing conversion of xanthine to uric acid. Xanthine has low urine solubility, and therefore xanthinuria may trigger xanthine crystalluria or urolithiasis. Besides allopurinol, differential diagnoses for xanthinuria include hereditary xanthinuria (Cavalier King Charles Spaniels) or excessive dietary purines. Prevention involves low purine intake, high water intake, and urine alkalinization to reduce urine xanthine concentration and increased its solubility. It is unclear why the dog had highly alkaline urine. It could be due to alkalinization in an attempt to dissolve the stone, or a false increase in pH due to contamination of cleaning solution. Xanthine urolithiasis has been reported in cats, dogs, and people. Information on solubility of xanthine crystals in the literature is lacking, but solubility results in the present case suggest that they may be significantly different than urate crystals and important in differentiating these crystals."

Urolithiasis. Joseph W. bartges, Amanda J. Callens. Vet. Clin. Sm. Anim. July 2015; doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2015.03.001. Quote: Urolithiasis occurs commonly in dogs and cats, and most uroliths occur in the lower urinary tract. More than 80% to 90% of lower urinary tract uroliths are struvite or calcium oxalate. Some uroliths, such as struvite, cysteine, and urate, are amenable to medical dissolution, whereas others, such as calcium oxalate, are not. ... In dogs, feeding a protein-restricted and sodium-restricted alkalinizing diet has been shown to decrease recurrence of calcium oxalate uroliths. ... In dogs and cats without underlying liver disease, dissolution may be attempted. Dissolution of urate uroliths in dogs is accomplished by feeding a purine-restricted, alkalinizing, diuresing diet and administering the xanthine oxidase inhibitor, allopurinol (15 mg/kg by mouth every 12 hours)80,92–96; allopurinol has not been evaluated in cats and should not be used. Although renal failure diets are protein restricted and thus lower in purines, there are 2 commercially available diets formulated to be low in purines: Prescription Diet u/d (Hill’s Pet Products) and UC Low Purine (Royal Canin). Canned diets may be better than dry diets. ... Xanthine Xanthine urolithiasis may occur with allopurinol administration to dogs, especially when dietary purines are not restricted. Management involves adjusting dosage of allopurinol and changing diet. ... Xanthine uroliths have also been found in a few Cavalier King Charles spaniels.No medical dissolution protocol for naturally occurring xanthine uroliths exists. Prevention involves feeding a purine-restricted, alkalinizing, diuresing diet. Without preventive measures, xanthine uroliths often recur within 3 to 12 months after removal.

Ureteral implantation using a three-stitch ureteroneocystostomy: description of technique and outcome in nine dogs. K. M. Pratschke. J. Sm. Anim. Pract. September 2015;56(9):566-571. Quote: Objective: To report the procedure, postoperative outcome and complications of a new technique for ureteral implantation by means of a three-stitch ureteroneocystostomy in dogs. Materials & Methods: Clinical records of dogs requiring ureteral implantation between April 2007 and June 2013 were retrospectively reviewed. Data retrieved included signalment, preoperative biochemistry results, details of the surgical procedure, perioperative and postoperative complications, postoperative biochemistry results and outcome. Results: Nine dogs [including a female neutered cavalier King Charles spaniel with left ureteral obstruction by suspected inflammatory granuloma and concurrent follicular cystitis] fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Follow-up times ranged from 10 to 79 months (median 30 months), with 8 of 9 dogs having an excellent long-term outcome and no major postoperative complications. One dog with follicular cystitis as a comorbidity developed obstruction from inflammatory granuloma and required revision surgery. Clinical Significance: The three-stitch technique for ureteral implantation compares favourably to previously documented techniques in terms of outcome and complication rates. Reduced tissue handling and a decreased volume of suture material may be beneficial for healing. The technique is also faster than previously described options, which may be of benefit in unstable patients requiring ureteral implantation due to traumatic injury or rupture.

Adverse urinary effects of allopurinol in dogs with leishmaniasis. M. Torres, J. Pastor, X. Roura, M. D. Tabar, Espada, A. Font, J. Balasch, M. Planellas. J. Sm. Anim. Pract. June 2016;57(6):299-304. Quote: Objective: The objective of this study was to describe the adverse effects of allopurinol on the urinary system during treatment of canine leishmaniasis. Methods: Retrospective case series of 42 dogs that developed xanthinuria while receiving allopurinol treatment for leishmaniasis. Results: Of 320 dogs diagnosed with leishmaniasis, 42 (13%) developed adverse urinary effects. Thirteen (of 42) dogs (31%) developed xanthinuria, renal mineralisation and urolithiasis; 11 (26·2%) showed xanthinuria with renal mineralisation; 9 (21·4%) had xanthinuria with urolithiasis and 9 (21·4%) developed xanthinuria alone. Urinary clinical signs developed in 19 dogs (45·2%). Clinical Significance: This study demonstrates that urolithiasis and renal mineralisation can occur in dogs receiving allopurinol therapy. Dogs receiving therapy should be monitored for the development of urinary adverse effects from the beginning of treatment.

Three Diverse Mutations Underlying Canine Xanthine Urolithiasis. Eva Furrow, Nicole Tate, Katie Minor, James Mickelson, Kasey Peterson, Jody Lulich. J. Vet. Int. Med. June 2016. 2016 ACVIM Forum Research Report Program. Quote: Hereditary xanthinuria in people is an autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) or molybdenum cofactor sulfurase (MOCOS). There are rare reports of hereditary xanthinuria in dogs, but genetic investigations have not previously been described. The objective of this study was to identify mutations underlying risk for canine xanthine urolithiasis by sequencing XDH and MOCOS in affected dogs. Five dogs with primary xanthine urolithiasis (i.e. no history of xanthine dehydrogenase inhibitor therapy) were recruited. This group included 2 Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS), 2 Toy Manchester Terriers (TMT), and a mixed-breed dog. Three homozygous mutations were identified. The CKCSs had a mutation resulting in a premature stop codon in MOCOS, the TMTs had a splice site mutation in MOCOS, and the mixed breed dog had a splice site mutation in XDH. cDNA sequencing confirmed exon skipping for the splice site mutations. Mutation-specific assays were developed to genotype 108 CKCSs and 50 TMTs without a history of urolithiasis. Of the 108 CKCS, 105 were clear, 3 were carriers, and none were homozygous for the CKCS mutation. Of the 49 TMTs, 37 were clear, 10 were carriers, and 2 were homozygous for the TMT mutation. Urine was analyzed from the 2 homozygous TMTs and revealed xanthinuria. In conclusion, diverse mutations underlie canine hereditary xanthinuria. Genetic testing can help inform breeders and identify dogs that may benefit from preventative therapies. Future studies are needed to determine mutation frequencies in other breeds and whether clinical outcome differs between the mutations. See, also: Three diverse mutations underlying canine xanthine urolithiasis. J. Animal Sci. September 2016;94(7supp4):163(P6030). N. M. Tate, K. M. Minor, J. R. Mickelson, K. Peterson, J. P. Lulich, E. Furrow. Quote: Hereditary xanthinuria in people is an autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) or molybdenum cofactor sulfurase (MOCOS). There are rare reports of hereditary xanthinuria in dogs, but genetic investigations have not previously been described. The purpose of this study was to uncover mutations underlying risk for canine xanthine urolithiasis by sequencing XDH and MOCOS in genomic DNA from affected dogs. The affected dogs included two Toy Manchester Terriers (TMT), two Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS), and a mixed breed dog. Three putative causal mutations were found. The TMT dogs had a homozygous splice site mutation in MOCOS, the CKCS dogs had a homozygous nonsense mutation in MOCOS, and the mixed breed dog had a homozygous splice site mutation in XDH. cDNA sequencing verified aberrant splicing for the two splice site mutations. Mutation assays were developed to determine the allele frequencies of the mutations in populations of TMT and CKCS dogs without a history of xanthine urolithiasis. Of 49 TMT dogs tested, 37 were clear, 10 were carriers, and 2 were homozygous for the TMT mutation. Urine was analyzed from the 2 homozygous TMTs and revealed xanthinuria. Of 108 CKCS dogs tested, 105 were clear, 3 were carriers, and none were homozygous for the CKCS mutation. In conclusion, diverse mutations were found to be responsible for hereditary xanthinuria in dogs, and we have developed genetic tests for these forms of the disease. Genetic testing can help inform breeders and identify dogs that may benefit from preventative therapies.

ACVIM Small Animal Consensus Recommendations on the Treatment and Prevention of Uroliths in Dogs and Cats. J.P. Lulich, A.C. Berent, L.G. Adams, J.L. Westropp, J.W. Bartges, C.A. Osborne. J. Vet. Int. Med. September 2016;30(5):1564-1574. Quote: In an age of advancing endoscopic and lithotripsy technologies, the management of urolithiasis poses a unique opportunity to advance compassionate veterinary care, not only for patients with urolithiasis but for those with other urinary diseases as well. The following are consensus-derived, research and experience-supported, patient-centered recommendations for the treatment and prevention of uroliths in dogs and cats utilizing contemporary strategies. Recommendation 3.3a: Feeding High-Sodium (>375 mg/100 kcal) Dry Foods should not be a Recommended as a Substitute for High-Moisture Foods. Rationale: High-sodium foods increase urinary water excretion, but the effects appear to be short-lived (ie, 3–6 months). Although the extent of water intake and urine dilution achieved with increased dietary salt might not be similar to that observed with high-moisture foods, it can be considered in dogs and cats in which owners decline to feed high-moisture foods. ... Recommendation 3.4.a: Consider Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors for Dogs Homozygous for Genetic Hyperuricosuria that have Failed Therapeutic Diet Prevention: Rationale: Urate urolith recurrence is common, especially in dogs with a genetic mutation in the urate transporter. Prevention may require more than dietary adjustments. The dosage of allopurinol to sufficiently prevent urate urolith recurrence without xanthine urolith formation is variable and influenced by the severity of disease, endogenous purine production, quantity of purines in the diet, urine pH, and urine volume. In a case series of 10 dogs with previous urate urolithiasis, allopurinol administration in excess of 9-38 mg/kg/d was associated with xanthine urolith formation. This occurs because allopurinol inhibits the metabolism of xanthine to uric acid and because xanthine is less soluble in urine than is uric acid. Based on these observations, we recommend a dosage of 5-7 mg/kg q12-24 h to safely prevent urate uroliths. The role and effectiveness of allopurinol and newer-generation xanthine oxidase inhibitors in patients with porto-vascular shunts are unknown. Administration of xanthine oxidase inhibitors should be avoided in dogs that are not receiving decreased purine diets to minimize the risk of xanthine urolith formation. ... Recommendation 3.5: To Minimize Cystine Urolith Recurrence, Decrease Urine Concentration, Limit Animal Protein Intake, Limit Sodium Intake, Increase Urine PH, and Neuter . ... Ultimately, we hope that these recommendations will serve as a foundation for ongoing and future clinical research and inspiration for innovative problem solving.

Evaluating urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) as a biomarker of myxomatous mitral valve disease in cavalier King Charles spaniels. L.B. Christiansen, S.E. Cremer, A. Helander, T.Madsen, M.J. Reimann, J.E. Møller, K. Höglund, I. Ljungvall, J. Häggström, L.H. Olsen. ECVIM 26th Congress; ESVC-O-25. September 2016. J. Vet. Int. Med. January 2017. Quote: Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is the most common heart disease in dogs with a high prevalence among Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS). Valvular changes may cause mitral regurgitation (MR) and over time, some dogs can progress into congestive heart failure. Increased circulating concentrations of serotonin are suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of MMVD in CKCS. 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) is a serotonin metabolite excreted in urine. Urine 5-HIAA is commonly used in human medicine as a biomarker of serotonin-secreting tumors. The aim of the present study was to investigate if urinary 5-HIAA is associated with MMVD severity in CKCS. We hypothesized that the urine 5-HIAA concentration was increased in CKCS with MMVD and that urine 5-HIAA concentration would correlate with the serotonin concentration in serum or plasma. Serum, plasma and urine samples were collected from 80 dogs above 4 years of age divided into four groups: control dogs (Beagles) with no evidence of heart disease (CON, n = 17), CKCS with no or minimal MR due to MMVD (nMR, n = 18), CKCS with mild MR due to MMVD (mMR, n = 22) and CKCS with moderate to severe MR due to MMVD (sMR, n = 23). Urinary 5-HIAA was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and creatinine (to correct for variations in urine dilution) by the Jaffe method. Serotonin concentrations in serum and platelet poor plasma were determined by a validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The results from preliminary analyses in a subset of dogs from three of the four groups (CON, nMR and sMR) with a mean age of 8.5 years (range: 4.1–13.3) are presented as the median (25–75% interquartile range). Analyses of the remaining samples are ongoing. No significant difference in urinary 5-HIAA to creatinine ratio (5-HIAA/CREA, lmol/mmol) was found between the CON dogs (n = 6; 2.37(1.52-2.58)), nMR dogs (n = 6; 2.77 (2.23–3.20)) and sMR dogs (n = 6; 2.94 (1.65–3.32)) (overall P = 0.48). Female dogs (n = 11) showed significantly higher 5-HIAA/CREA than male dogs (n = 7; 3.05 (2.47–3.32) versus 1.65 (1.50–2.49), P = 0.011). The preliminary data did not reveal any association of 5-HIAA/CREA with age (P = 0.844; R2=0.003), serum serotonin concentration (P = 0.396; R2=0.045) or plasma serotonin concentration (P = 0.3801; R2=0.048). In conclusion, the preliminary data indicate that urinary 5-HIAA concentrations are dependent on the sex, but not the age of the dog. Further analyses are necessary to draw final conclusions regarding the possible associations between urinary 5-HIAA concentrations and MMVD severity in dogs. (See also this June 2019 article.)

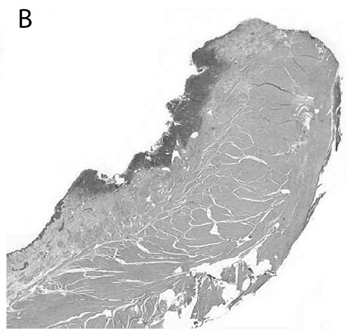

The dog as an animal model for bladder and urethral urothelial carcinoma:

Comparative epidemiology and histology. Simone de Brot, Brian D.

Robinson, Tim Scase Llorenç Grau‑Roma, Eleanor Wilkinson, Stephen A.

Boorjian, David Gardner, Nigel P. Mongan. Oncology Letters. May 2018; doi:

10.3892/ol.2018.8837. Quote: Despite the recent approval of several novel

agents for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma (UC), survival in

this setting remains poor. As such, continued investigation into novel

therapeutic options remains warranted. Pre‑clinical development of novel

treatments requires an animal model that accurately simulates the disease in

humans. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the dog as an animal

model for human UC. A total of 260 cases of spontaneous, untreated canine

primary urethral and urinary bladder UC, were epidemiologically and

histologically assessed and classified based on the current 2016 World

Health Organization (WHO) tumor classification system. Canine data was

compared with

human

data available from scientific literature. The mean age of dogs diagnosed

with UC was 10.22 years (range, 4‑15 years), which is equivalent to 60‑70

human years. The results revealed a high association between UC diagnosis

with the female sex [odds ratio (OR) 3.51; 95% confidence interval (CI)

2.57‑4.79; P<0.001], surgical neutering (OR 4.57; 95% CI 1.87‑11.12;

P<0.001) and breed (OR 15.11 for Scottish terriers; 95% CI 8.99‑25.41;

P<0.001). Based on the 2016 WHO tumor (T), node and metastasis staging

system, the primary tumors were characterized as T1 (38%), T2a (28%), T2b

(13%) and T3 (22%). Non‑papillary, flat subgross tumor growth was strongly

associated with muscle invasion (OR 31.00; P<0.001). Irrespective of

subgross growth pattern, all assessable tumors were invading beyond the

basement membrane compatible with infiltrating UC. Conventional, not further

classifiable infiltrating UC was the most common type of tumor (90%),

followed by UC with divergent, squamous and/or glandular differentiation

(6%). Seven out of the 260 (2.8%) cases were classified as non‑urothelial

based on their histological morphology. These cases included 5 (2%) squamous

cell carcinomas, 1 (0.4%) adenocarcinoma and 1 (0.4%) neuroendocrine tumor.

The 2 most striking common features of canine and human UC included high sex

predilection and histological tumor appearance. The results support the

suitability of the dog as an animal model for UC and confirm that dogs also

spontaneously develop rare UC subtypes and bladder tumors, including

plasmacytoid UC and neuroendocrine tumor, which are herein described for the

first time in a non‑experimental animal species. (Image (B) above is a

microphotograph of a flat urothelial carcinoma in the urinary bladder in an

11-year-old male neutered Cavalier King Charles spaniel.)

human

data available from scientific literature. The mean age of dogs diagnosed

with UC was 10.22 years (range, 4‑15 years), which is equivalent to 60‑70

human years. The results revealed a high association between UC diagnosis

with the female sex [odds ratio (OR) 3.51; 95% confidence interval (CI)

2.57‑4.79; P<0.001], surgical neutering (OR 4.57; 95% CI 1.87‑11.12;

P<0.001) and breed (OR 15.11 for Scottish terriers; 95% CI 8.99‑25.41;

P<0.001). Based on the 2016 WHO tumor (T), node and metastasis staging

system, the primary tumors were characterized as T1 (38%), T2a (28%), T2b

(13%) and T3 (22%). Non‑papillary, flat subgross tumor growth was strongly

associated with muscle invasion (OR 31.00; P<0.001). Irrespective of

subgross growth pattern, all assessable tumors were invading beyond the

basement membrane compatible with infiltrating UC. Conventional, not further

classifiable infiltrating UC was the most common type of tumor (90%),

followed by UC with divergent, squamous and/or glandular differentiation

(6%). Seven out of the 260 (2.8%) cases were classified as non‑urothelial

based on their histological morphology. These cases included 5 (2%) squamous

cell carcinomas, 1 (0.4%) adenocarcinoma and 1 (0.4%) neuroendocrine tumor.

The 2 most striking common features of canine and human UC included high sex

predilection and histological tumor appearance. The results support the

suitability of the dog as an animal model for UC and confirm that dogs also

spontaneously develop rare UC subtypes and bladder tumors, including

plasmacytoid UC and neuroendocrine tumor, which are herein described for the

first time in a non‑experimental animal species. (Image (B) above is a

microphotograph of a flat urothelial carcinoma in the urinary bladder in an

11-year-old male neutered Cavalier King Charles spaniel.)

Effects of a Watermelon Extract Beverage on Canine Lipid Metabolism and Urine Crystals. Sayaka Miyai, Toshiharu Hashizume, Toshio Okazaki. Anim. & Vet. Sci. November 2018;6(5):74-79. Quote: Previous report showed that watermelon consumption has an anti-obesity effects in rats. The purpose of this study is to examine the effects on body weight, body fat percentage, serum biochemical data, serum adipokine concentrations (leptin, adiponectin, and resistin), urine specific gravity and sediments when 12 dogs were given watermelon extract beverage instead of water for 3 months. Those data were all assessed before the study period and again at 1.5 and 3 months. Although there were no remarkable changes in most of these parameters, a significant decrease in serum leptin concentrations at 1.5 and 3 months. Calcium oxalate and struvite crystals were observed in the urinary sediment in five dogs; although their urine specific gravities remained >1.040 throughout, the number of urinary crystals had decreased by the end of the 3-month period. Morphological components were not found in the urinary sediment of the other five dogs; their urine specific gravities were also >1.040 before the study period and at 1.5 months, but these had decreased to <1.040 at 3 months. These results suggested that drinking the watermelon extract beverage reduced serum leptin levels and inhibited the formation of urine crystals such as calcium oxalate and struvite crystals in dogs.

Urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in Cavalier King Charles spaniels with preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease. L.B.Christiansen, S.E.Cremer, A. Helander, Tine Madsen, M.J. Reimann, J.E. Møller, K. Höglund, I. Ljungvall, J. Häggström, L. Høier Olsen. Vet. J. August 2019;250(1):26-43. Quote: Higher concentrations of circulating serotonin have been reported in Cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCS) compared to other dog breeds. The CKCS is also a breed highly predisposed to myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD). The aim of this study was to determine urine concentrations of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), the major metabolite and excretion product of serotonin, in a population of CKCS with preclinical MMVD, and to evaluate whether urine 5-HIAA concentrations were associated with MMVD severity, dog characteristics, setting for urine sampling, platelet count, and serotonin concentration in serum and platelet-poor plasma (PPP). The study population consisted of 40 privately-owned CKCS (23 females; 17 males) with and without preclinical MMVD as follows: American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) group A (n=11), ACVIM group B1 (n=21) and ACVIM group B2 (n=8). ... CKCS were classified into clinical disease severity groups according to the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) guidelines. In brief, CKCS with no auscultatory murmur and/or normal echocardiogram (MR < 20%) were classified as ACVIM group A, while CKCS with a characteristic left apical systolic mitral regurgitation murmur and/or a MR ≥ 20% were classified as ACVIM group B1 if no remodelling of the heart was evident, or ACVIM group B2 if remodelling of LA (LA/Ao ≥ 1.6) and left ventricle (LVIDDN ≥ 1.7) were detected. ... Urine 5-HIAA concentrations were not significantly associated with preclinical MMVD disease, platelet count or circulating concentrations of serotonin (in serum and PPP; P>0.05). Females had higher 5-HIAA concentrations than males in morning urine collected at home (females, 3.1 [2.9-3.7] µmol/mmol creatinine [median and quartiles]; males, 1.7 [1.2-2.2] µmol/mmol creatinine; P=0.0002) and urine collected at the clinic (females, 3.5 [3.1-3.9] µmol/mmol creatinine; males, 1.6 [1.3-2.1] µmol/mmol creatinine; P<0.0001). Five-HIAA concentrations in urine collected at home and at the clinic were significantly associated (P=0.0004; r=0.73), and higher concentrations were found in urine collected at the clinic (P=0.013). Urine 5-HIAA concentration was influenced by sex and setting of urine sampling. Urine 5-HIAA concentration was not associated with MMVD severity or circulating concentrations of serotonin in CKCS with preclinical disease. Highlights: •Urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) concentrations predict progression of cardiac disease in some human conditions. •Urine 5-HIAA was measured in cavalier King Charles spaniels (CKCS) with preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD). •Urine 5-HIAA concentrations were higher in clinic-collected samples than in morning, home-collected samples. •Female CKCS showed higher urine 5-HIAA concentrations than male dogs. •Urine 5-HIAA concentrations were not associated with disease severity in CKCS with preclinical MMVD. (See also this January 2017 abstract.)

Urolithiasis in Small Animals. Alice Defarges, Michelle Evason, Marilyn Dunn, Allyson Berent. Clinical Small Animal Internal Medicine, Chap. 123. April 2020; doi: 10.1002/9781119501237.ch123. Quote: Formation of urinary calculi (uroliths) has been hypothesized to occur through multiple mechanisms or processes. Three of the more common of these theories are the precipitation‐crystallization theory, the matrix‐nucleation theory, and the crystallization‐inhibition theory. Urine is commonly supersaturated with crystalloids, and this is a prerequisite for urolith formation. Factors that predispose to urine stasis also play an important role in urolithiasis formation. Risk factors for calcium oxalate uroliths in dogs include sex, and they occur more commonly in male than female dogs. ... Xanthine is an important mediator in purine metabolism; the drug allopurinol binds rapidly to (and inhibits the action of) xanthine oxidase, thereby decreasing conversion of hypoxanthine to xanthine and xanthine to uric acid. The result is a reduction of serum and urine concentrations of uric acid, with an increase in serum and urine concentrations of xanthine. As such, most xanthine uroliths in dogs form secondary to therapy with allopurinol via this mechanism. This is particularly true when a diet high in purines (meat based) is fed to these at‐risk dogs. Naturally occurring xanthinuria has been reported in Cavalier King Charles spaniels and dachshunds, and is thought to reflect an inborn error of xanthine oxidase activity. ... Hepatic dysfunction is associated with a reduced ability to convert ammonia to urea and uric acid to allantoin. Therefore, dogs suffering from hepatic dysfunction may develop hyperammonuria and hyperuricuria, which may result in urate urolith formation. Urolithiasis typically induces inflammatory urine sediment, such as pyuria (presence of white blood cells), hematuria (red blood cells), and proteinuria.

Is there a link between bacteriuria and a reversible encephalopathy in dogs and cats? A. H. Crawford, T. J. A. Cardy. J. Sm. Anim. Pract. August 2020; doi: 10.1111/jsap.13178. Quote: Bacteriuria has been associated with abnormal neurological status in humans, especially geriatric patients. In this report, we review 11 cases (seven dogs [including two cavalier King Charles spaniels] and four cats) that support an association between bacteriuria and abnormal neurological status in veterinary medicine. These cases showed diffuse forebrain signs with or without brainstem signs, but primary brain disease was excluded by MRI and cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Bacteriological culture of urine was positive in each animal and neurological deficits improved or resolved with initiation of antibiosis ± fluid therapy and levetiracetam. ... Case 5: 11.5 year old female neutered CKCS; symptoms: acute onset of abnormal episodes consisting of head nodding, tremors, swaying and collapse lasting a few seconds, and occurring approximately 15 times per day; urine culture: Staph pseudointermedius; MRI of head: normal; treatment: 14 days of amoxicillin clauvulanate, then 14 days of levetiracetam; outcome: resolution of obtundation with treatment, neurologically normal at follow up 4 months later). Case 6: 5.5 year old male neutered CKCS; symptoms: Acute onset of disorientation, progressive obtundation, inappetance, five focal seizures in the 12 hours prior to referral (Last seizure 5 hours prior to presentation); urine culture: E. coli; MRI of head: mild ventriculomegaly and Chiari-like malformation; treatment: 14 days amoxicillin clavulanate; outcome: Gradual improvement in mentation after initiation of treatment, resolution of pollakiuria and dysuria within 48 hrs., negative urine culture 14 days after discharge, no further focal seizures and neurologically normal at time of follow up 3 months later. ... While further studies are needed to definitively confirm or refute the link between bacteriuria and a reversible encephalopathy, urine bacteriological culture should be considered in veterinary patients presented with acute onset forebrain neuro‐anatomical localisation, even in the absence of clinical signs of lower urinary tract inflammation.

Urolithiasis in dogs: Evaluation of trends in urolith composition and risk factors (2006‐2018). Lucy Kopecny, Carrie A. Palm, Gilad Segev, Jodi L. Westropp. J. Vet. Intern. Med. May 2021; doi: 10.1111/jvim.16114. Quote: Background: Urolithiasis is a common and often recurrent problem in dogs. Objective: To evaluate trends in urolith composition in dogs and to assess risk factors for urolithiasis, including age, breed, sex, neuter status, urolith location, and bacterial urolith cultures. Sample Population: A total of 10,444 uroliths and the dogs from which they were obtained. Methods: The laboratory database at the UC Davis Gerald V. Ling Urinary Stone Analysis Laboratory was searched for all urolith submissions from dogs between January 2006 and December 2018. Mineral type, age, breed, sex, neuter status, urolith location, and urolith culture were recorded. Trends were evaluated and variables compared to evaluate risk factors. Results: Calcium oxalate (CaOx) and struvite‐containing uroliths comprised the majority of all submissions from dogs, representing 47.0% and 43.6%, respectively. The proportion of CaOx‐containing uroliths significantly decreased from 49.5% in 2006 to 41.8% in 2018, with no change in the proportion of struvite‐containing urolith submissions. Cystine‐containing uroliths comprised 2.7% of all submissions between 2006 and 2018 and a significant nonlinear increase in this mineral type occurred over time (1.4% of all submissions in 2006 to 8.7% in 2018). Of all cystine‐containing uroliths, 70.3% were from intact male dogs. Age, breed, and sex predispositions for uroliths were similar to those previously identified. ... Xanthine: Breed predispositions were not determined because of the small numbers of dogs with xanthine‐containing uroliths. Of dogs with xanthine‐containing uroliths where breed was reported, 9/25 (36.0%) were Dalmatians, 5/25 (20.0%) were mixed breed dogs and 3/25 (12.0%) were Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. ... Few xanthine‐containing uroliths were submitted, most often from the Dalmatian and Cavalier King Charles Spaniel breeds. ... The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel is recognized as having familial xanthinuria. ... Conclusions and Clinical Importance: Although calcium oxalate‐ and struvite‐containing uroliths continue to be the most common uroliths submitted from dogs, a decrease in the proportion of CaOx‐containing uroliths and an increase in the proportion of cystine‐containing uroliths occurred during the time period evaluated.