Epilepsy and Other Seizures in

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels

-

Seizures,

In General

Seizures,

In General - What Epilepsy Is

- Symptoms

- Other Seizure Disorders

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Breeders' Responsibilities

- What You Can Do

- Research News

- Related Links

- Veterinary Resources

The topic of epilepsy discussed here also includes several different types of seizures and not just the classic idiopathic epilepsy (IE) which is prevalent in cavalier King Charles spaniels.

Seizures, In General

A seizure is a sudden, uncontrolled electrical disturbance in the dog’s brain, that causes behavioral changes. They are classified in two main types, generalized and focal, based upon their signs and and the brain areas affected.

Seizures can be caused by a variety of factors, which also are classified either as primary or secondary to some other underlying cause. Primary seizures include idiopathic epilepsy, meaning that the seizure has no known underlying cause and may be hereditary. Secondary seizures are caused by some identifiable underlying health condition, which may include (1) metabolic disorders (low blood sugar, imbalance in the body chemistry); (2) neurological disorders (brain abnormalities); (3) electrolyte imbalances (abnormal electrolyte levels affecting neuronal functions); (4) trauma to the head; (5) infections in the brain (meningitis, encephalitis); (6) exposure to toxins (chemicals, plants, medications).

Flea and tick treatments which contain isoxazolines can increase the likelihood that dogs susceptible to seizures will experience them. Isoxazolines lower the threshold of seizures. These flea and tick products include Bravecto, Credelio, Nexgard, Revolution Plus, and Simparica Trio.

What Epilepsy Is

Epilepsy is a disease of the dog's brain, which results in repeated physical attacks, called seizures. In dogs, a seizure is caused by an undesired signal sent from the brain through the nervous system to the muscles, resulting in uncontrolled shaking, twitching, often unconsiousness, and occasionally loss of senses and unintentional behaviors. While the brain sends the signal, that does not mean that the brain is the underlying cause of the seizure.

A form of epilepsy, called "idiopathic epilepsy" (IE), is inheritable. While the common definition of "idiopathic" means that the cause is unknown, in veterinary medicine it means that it is a recognized syndrome where there appears to be no structural abnormality. Idiopathic epilsepsy means that it is a disorder that is independent of other disorders or causes (sui generis). IE is believed to be caused by a mutation in a specific gene which the dogs have inherited from their parents. IE is the most common chronic neurological disorder in dogs and is prevalent in cavalier King Charles spaniels.*

* See Neurological diseases of the Cavalier King Charles spaniel.

Because by definition, idiopathic epilepsy's cause is unknown, reseachers have examined IE in dogs with other disorders, called comorbidities or concurrent conditions, such as urinary tract infections. To complicate this issue further, some anti-seizure medications (ASM), such as phenobartital, may have side effects that mimic or cause such concurrent conditions.

According to a June 2004 report, idiopathic epilepsy has been found to occur more frequently in descendants from bloodlines originating from whole-colored CKCS ancestors from the late 1960s, especially from matings of blood relatives, such as half-siblings. See also a follow up report in July 2005.

In a 2012 report, UK neurology researchers examined the magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of 85 cavaliers, looking for a relationship between Chiari-like malformation (CM), ventriculomegaly, and seizures in the dogs. The 85 CKCSs all had CM; 27 of them also had had seizures. They found no association between CM, ventriculomegaly, and the seizures. The seizures were classified as having partial onset -- meaning that they occur in in one area of the brain, unlike generalized seizures which typically affect nerve cells throughout the brain -- in 61% of the dogs. They also stated that "Another cause of recurrent seizures in CKCS (such as familial epilepsy) is suspected, as previously reported."

RETURN TO TOP

Symptoms

There are many different types of seizures in dogs. Common signs include:

• Collapsing or falling – with or without loss of consciousness

• Uncontrolled movements – jerking or twitching movements of the head, legs, or entire body

• Stiffness – a rigid posture of the legs and/or entire body, usually lying on a side, with an arched back

• Paddling or running motions – while lying on a side

• Vocalizations – barking, whining, or howling

• Loss of bladder or bowel control — Involuntary • urination or defecation

The most common is the generalized major motor seizure, characterized by paddling of the limbs. (See photo at upper right.) The dog may cry, bark or whine during the seizure, and it may snap or bite, not quite fully aware of its surroundings. Urination and defecation are common during a generalized seizure.

A brief seizure, called the absence seizure, may last for only seconds, during which the dog may just seem to be staring into space. Other seizures may be localized to only certain parts of the dog's body, called focal seizures, such as head nodding or twitching of the face. Such seizures which continue for over 5 minutes are called Status Epilepticus (SE). Another version of SE is if more than one seizure event occurs within 5 minutes. Some SE seizures may last for over a half hour.

The most severe of seizures, once called a grand mal seizure, is a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, (GTCS) which has two phases of muscle activity, a "tonic" phase (stiffening) and a "clonic" phase (twitching or jerking). Such seizures may progress to SE. See this June 2022 article about a cavalier with GTCS.

![]() See this

YouTube video of a Tibetan spaniel experiencing a seizure. The onset of epilepsy in cavaliers is most common between the ages of six

months and five years.

See this

YouTube video of a Tibetan spaniel experiencing a seizure. The onset of epilepsy in cavaliers is most common between the ages of six

months and five years.

Post seizural signs may last from a few minutes to an hour. It usually takes about 30 minutes for a dog to appear to have fully recovered from epileptic convulstions of a seizure. Any seizure lasting more than five minutes would be an emergency case requiring immediate veterinary care. If the dog remains unconscious following convulsions, that sign also calls from immediate care.

The most common form of hereditary epilepsy in cavaliers is flycatcher's syndrome which is discussed on its own webpage.

RETURN TO TOP

Other Seizure Disorders

- Canine Cognitive Dysfunction

- Encephalitis

- Environmental Causes

- Flycatcher's Syndrome

- Myoclonus

- Oligodendroglioma

- Vestibular Syndrome

Here we describe disorders other than epilepsy but which may include seizures among their signs and symptoms.

Canine Cognitive Dysfunction

Canine cognitive dysfunction (CCD) is the term which describes behavioral changes resulting in impairment of such qualities as awareness, perception, reasoning, and judgment. In dogs, it may be indicated by anxiety, disorientation in familiar places, altered sleep-wake cycles, reduced activity, "sundowning" (agitation, restlessness, pacing, barking in evenings and nights), interior urination and/or defecation. CCD episodes may be temporary or permanent and static or progressive. In dogs having epileptic seizures, CCD is common in idiopathic epilepsy (IE) and may be concurrent with their onset and/or continuation, but CCD may also be independent of such seizures. Epilepsy is believed to have a role in cognitive decline. See this February 2018 article and this January 2020 article.

Encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain, and autoimmune encephalitis occurs when the dog's immune system mistakenly attacks healthy brain cells, leading to that inflammation. GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, which enables the regulation of neuronal activity. GABAAR are ion channels in the brain control the rapid transmission of nerve impulses between neurons.

In a June 2022 article, German veterinary neurologists described the first reported case of a dog -- a 1-year-old cavalier -- diagnosed with anti-GABAAR (γ-aminobutyric acid-A receptor) autoimmune encephalitis. The cavalier (right) had multiple generalized seizures and showed alternating stupor and hyperexcitability, ataxia, repetitive muscle contractions, and circling to the left side. Auto-antibody encephalitis, with antibody-mediated dysfunction of receptors was suspected. Despite treatment with multiple antiseizure medications (diazepam followed by phenobarbital) the seizures and behavior abnormalities continued, and the dog alternated between stupors and hyperexcitability. Immunotherapy with dexamethasone, a corticosteroid, led to rapid improvement of the clinical signs and the CKCS improved continuously. A month later, GABAAR auto-antibodies had decreased significantly. An antibody search in the cerebral-spinal fluid (CSF) and serum located a neuropil staining pattern of GABAAR antibodies. At the examination four weeks after the start of immunotherapy, the dog was clinically normal; the GABAAR antibody titer in serum had strongly decreased; and the antibodies were no longer detectable in the CSF. The clinicians report that this is "the first veterinary patient with an anti-GABAAR encephalitis with a good outcome following ASM and corticosteroid treatment." They concluded:

"Based on the clinical signs and presentation (epileptic seizures lacking any response to ASMs, erratic behavioral changes) and the results of the initial diagnostics (lack of abnormal findings on conventional MRI and CSF examination), an autoimmune encephalitis was suspected, proven, and successfully treated. Clinicians should consider to test for autoantibodies and start immunotherapy in cases with a similar clinical presentation and lack of response to anti-seizure medication even if an inflammatory/infectious or neoplastic cause was clinically excluded on MRI and CSF."

Environmental Causes

In a December 2021 article, a 4-month-old cavalier with localized seizures -- head nodding and eyelid twitching -- was suspected of epilepsy. However, further examination revealed that a grass seed was lodged within the gums near a molar tooth. Once the seed was surgically removed, the dog's clinical symptoms disappeared. The clinicians determined that an inflammatory reaction caused pain (neuralgia) at the trigeminal nerve, that resulted in the head nodding and twitching. They recommended that trigeminal neuralgia be considered as a differential diagnosis of facial seizures before starting any anti-epileptic treatments.

Flycatcher's Syndrome

Symptoms similar to those of idiopathic epilepsy may be due to other causes. It is to be distinguished from Flycatcher's Syndrome, which is a separate disorder of the CKCS. It also is to be distinguished from malformations of the skull, including either meningoencephalocele (MEC), which is a herniation of cerebral tissue and meninges through a defect in the cranium, or a meningocele (MC), a herniation of the meninges alone. See this January 2017 article.

Myoclonus

Myoclonus is a syndrome displaying symptoms of spasmodic jerky contractions of groups of muscles, mainly of the head (such as, rapid eye movements, nodding, or shuddering) and forelimbs when the dog is standing or sitting. The syndrome can be progressive with affected dogs suffering frequent jerks which may cause the dog to fall or stumble.

Oligodendroglioma

Oligodendroglioma is a tumor located in glial cells in the dog's brain. it is a common tumor in dogs and humans and is graded by the World Health Organization (WHO) by its severity and malignancy. WHO grade 2 tumors are called "low-grade", which typically grow slowly, and respond to treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. WHO grade 3 tumors are "high-grade" and are cancerous, aggressive, and spread rapidly.

In a 2022 abstract, the clinicians reported the case of a 9 month old female cavalier which had a 3 month history of sudden onset episodes of pain and scratching at the neck. The signs progressed over the following 3 years to generalized tonic-clonic epileptic seizures progressed within 48 hours to the point of stupor, cardiac arrest and death. Post-mortem examination revealed that the tumor was "an anaplastic oligodendroglioma (WHO grade III) with subarachnoidal and intraventricular drop metastasis".

Vestibular Syndrome

Vestibular syndrome symptoms may be confused with epileptic signs. In particular, vestibular epilepsy (VE) is described as focal seizures with vestibular disease as the only or main symptom. The signs range from mild disequilibrium to dizziness and vertigo. These seizures tend to have a short duration of even just a few seconds to minutes and an abrutp ending. Diagnosis of VE may be confused with vestibular paroxysmia (VP), a much rarer disorder among dogs. consisting of brief episodes of spinning or non-spinning vertigo. In this March 2024 article, VE was diagnosed in 10 dogs, including a cavalier King Charles spaniel. The episodes of VE in this study were recurrent, as may be epileptic seizures. See the linked article for details. Its authors suspect an epileptic origin for the VE episodes. See our Vestibular Disorders webpage.

RETURN TO TOP

Diagnosis

All

dogs should be examined by a veterinarian after their first seizure for

determination of the cause. Diagnosing epilepsy in dogs is difficult. It begins by attempting to rule out

other causes for the seizures. Some cases of epileptic seizures have a specific structural cause. The age of onset, breed, weight, historical findings, and

neurological exam findings are important in estimating the likelihood that there

is a structural problem and therefore a specific treatment and prognosis.

structural cause. The age of onset, breed, weight, historical findings, and

neurological exam findings are important in estimating the likelihood that there

is a structural problem and therefore a specific treatment and prognosis.

Video recordings of the dog during the event can be very helpful to the treating veterinarian in diagnosing the cause. The most useful type of video is of the dog moving about during the seizure event.

Since diagnosis of idiopathic epilepsy is largely a "rule out" effort, other tests would be performed to rule out other underlying causes. They include:

Blood tests

Urinalysis

Neurological examination

Metabolic disoders testing

Infectious diseases testing

Autoimmune encephalitis antibody titers

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis

DNA testing

Other possible disorders, such as vestibular

disease, may be diagnosed instead of epilepsy becasue their symptoms

can be similar in sume cases.

Other possible disorders, such as vestibular

disease, may be diagnosed instead of epilepsy becasue their symptoms

can be similar in sume cases.

The electroencephalogram (EEG) (right) is a frequently used device in diagnosing epilepsy. Electroencephalography uses electrodes that detect the flow of electrical current between the cells of the brain, spinal cord, heart, and other organs, to view brain function. EEG provides data regarding nerve cell activity. However, EEG has some serious drawbacks in animals.

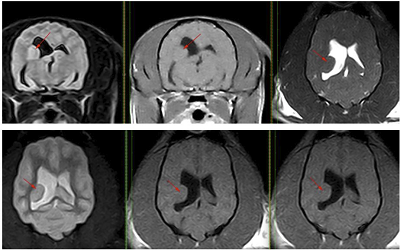

Advanced imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (left) or computed tomography (CT) scans, is necessary to be able to actually see the structure of the brain. By imaging the brain, veterinarians are able to diagnose diseases such as brain tumors or hydrocephalus (water on the brain) which can cause seizures. Essentially, MRI scans serve to rule out structural abnormalities. Veterinary neurologist Dr. Clare Rusbridge published two YouTube videos on MRI scanning epilepsy patients in May 2024. The first one is titled "Epileptic pet -- should I get a MRI?", and the second one is "MRI Epilepsy Protocol for pets: A Step-by-Step Guide".

In a September 2015 article, the International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force issued a consensus proposal on diagnosing epilepsy in dogs. They outlined "two fundamental steps: to establish if the events the animal is demonstrating truly represent epileptic seizures and if so, to identify their underlying cause." They then described a three-tier system for the diagnosis of idiopathic epilepsy (IE):

"Tier I confidence level for the diagnosis of IE is based on a history of two or more unprovoked epileptic seizures occurring at least 24 h apart, age at epileptic seizure onset of between six months and six years, unremarkable inter-ictal physical and neurological examination, and no significant abnormalities on minimum data base blood tests and urinalysis.

Tier II confidence level for the diagnosis of IE is based on the factors listed in tier I and unremarkable fasting and post-prandial bile acids, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (based on an epilepsy-specific brain MRI protocol) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis.

Tier III confidence level for the diagnosis of IE is based on the factors listed in tier I and II and identification of electroencephalographic abnormalities characteristic for seizure disorders. The authors recommend performing MRI of the brain and routine CSF analysis, after exclusion of reactive seizures, in dogs with age at epileptic seizure onset <6 months or >6 years, inter-ictal neurological abnormalities consistent with intracranial neurolocalisation, status epilepticus or cluster seizure at epileptic seizure onset, or a previous presumptive diagnosis of IE and drug-resistance with a single antiepileptic drug titrated to the highest tolerable dose. This consensus article represents the basis for a more standardised diagnostic approach to the seizure patient. These recommendations will evolve over time with advances in neuroimaging, electroencephalography, and molecular genetics of canine epilepsy."

RETURN TO TOP

Treatment

- primary drugs

- secondary drugs

- surgery

- natural alternative remedies

- dietary remedies

- neurostimulation

Any

seizure lasting more than five minutes would be an emergency case

requiring immediate veterinary care. If the dog remains unconscious

following convulsions, that sign also calls from immediate care.

Any

seizure lasting more than five minutes would be an emergency case

requiring immediate veterinary care. If the dog remains unconscious

following convulsions, that sign also calls from immediate care.

Immediately after a seizure, the dog should be handled with caution. The dog likely will pant after a seizure, due to heat generated by the intense brain activity and seizure. Cool, wet compresses place at the base of the skull and in the groin area will help decrease the body temperature. The dog should be offered a drink of water, but should not be left unattended with a water bowl.

The owner should keep a calendar noting the frequency of the seizures, and the dog that seizures more than once a month should treated long term with anti-convulsants. The patient on any of these drugs should be monitored closely for effectiveness and any adverse reactions. Monitoring includes frequent blood testing.

Medical treatment for frequent and/or long-lasting seizures should be started as quickly as possible, because such seizures can have serious consequences to the brain, heart, bladder, kidneys, and other essential organs.

Most of the medications described below are labeled "anti-seizure drugs (ASDs)" or "anti-seizure medications (ASMs)". Unfortunately, however, less than 50% of dogs treated with these anti-convulsants become seizure-free without significant side-effects. Typical adverse reactions to ASDs are: ataxia (loss of the ability to coordinate muscular movement), lethargy, increased thirst, and increased appetite. The ASDs associated with increased appetite have been phenobarbital, imepitoin, potassium bromide, zonisamide, and levetiracetam. These drugs are discussed in some detail below.

In general, the side effects from most conventional ASDs may reduce the dogs' quality of life, due to blood and liver toxicity. Periodic bloodwork monitoring to check for changes in liver conditions is recommended.

• primary drugs

The four drugss considered most effective in the initial treatment of epilepsy by many clinicans are phenobarbital (PB), potassium bromide (KBr), zonisamide (ZNS), and imepitoin. They are called "primary drugs" because one of them, or a combmination of them, is most frequently prescribed and in many cases may be the only treatment ever prescribed for affected dogs which respond well to them.

Medication will usually not eliminate seizures entirely, and is considered effective if a seizure occurs no more than every four to six weeks. Any time the dog exhibits a cluster of seizures, the veterinarian should be consulted, and may require immediate emergency treatment by the veterinarian, due to the possibility of permanent brain damage.

In an October 2014 report, UK researchers found evidence to support the efficacy of oral phenobarbital and imepitoin and a "fair level of evidence" to support the efficacy of oral potassium bromide and levetiracetam. However, for zonisamide, primidone, gabapentin, pregabalin, sodium valproate, felbamate, and topiramate, they found "insufficient evidence to support their use due to lack of bRCTs [blinded randomized clinical trials]". They concluded that "there is a need for greater numbers of adequately sized bRCTs evaluating the efficacy of AEDs [antiepileptic drugs] for IE."

Anti-convulsants (ASMs) do not always work. For example, in a June 2022 article, German veterinary clinicians report a case of a 1-year-old cavalier which had endured multiple generalized tonic-clonic epileptic seizures, episodic hyperexcitability alternating with episode of stupor, and intermittent left circling behavior. The CKCS did not respond to multiple ASMs -- diazepam followed by phenobarbital. An autoimmune encephalitis was suspected, and GABAAR antibodies were detected in his blood serum and cerebral-spinal fluid (CSF), confirming a diagnosis of anti-GABAA receptor encephalitis. The cavalier recovered following treatment of immunotherapy with corticosteroids.

Phenobarbital

Oral phenobarbital (PB) (Epiphen, Soliphen, Solfoton, Luminal, Phenoleptil) may be started once the seizures recur frequently. This drug lowers the neuron activity in the dog’s brain. It probably is the most effective drug, particularly for dogs suffering from severe epilepsy (having a tonic-clonic seizure or grand mal seizue more frequently than every two months). The usually starting dose is 3mg/kg every 12 hours. Administering this drug requires blood sampling periodically, starting at 2 weeks following the first dose. Phenobarbital has potential adverse effects, including drowsiness, inactivity, loss of coordination (ataxia), increased appetite and weight gain, and liver enzyme issues. Daily doses should not exceed 12 mg/kg to avoid liver dysfunction. The range of serum concentration should be 120-130 µmol/l (25-35 mg/l).

For more information on phenobarbital in treating epilepsy, watch this YouTube video by Dr. Clare Rusbridge.

In a February 2016 report, an international panel of veterinary neurologists and other specialists published a "2015 ACVIM Consensus Statement" on seizure management in dogs based on current literature and clinical expertise, authorized by the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM). In that report, they rated phenobarbital, "High recommendation and likely be effective treatment."

Potassium bromide (KBr)

Another anti-convulsant medication is potassium bromide (KBr) (Bromav, Epilease, KBroVet-ca1, Libromide). In the February 2016 report in which an international panel of veterinary neurologists and other specialists published a "2015 ACVIM Consensus Statement" on seizure management in dogs based on current literature and clinical expertise, those authors gave potassium bromide a "Moderate recommendation and most likely to be effective treatment."

KBr does not cause liver problems because it is eliminated by the kidneys. Common side effects are increased drinking and urination, increased appetite and weight gain, sedation, and a wobbly gait, mainly in the rear legs.

Excessive intake of bromide may result in bromide toxicity, resulting in severe paralysis and twitching and excessively high levels of chlorine in the blood stream. See this section on bromide toxicity for a discussion of veterinary journal articles reporting bromide toxicity in cavaliers.

In an April 2014 report, a cavalier suffered loss of muscle control and repetitive leg twitching due to an overdose of potassium bromide. Also, 30% of dogs treated with these drugs still will demonstrate poor seizure control or chronic resistance to the drugs.

Zonisamide

Zonisamide (ZNS) (Zonegram) is an anticonvulsant which in clinical trials appears to be effective for generalized seizures in dogs. It’s anti-seizure effect is believed to work through sodium and calcium channels. The 2015 ACVIM Consensus Statement rated zonisamide, "Low recommendation and may not be effective treatment." A May 2024 article concluded that zonisamide "is effective and well-tolerated in dogs with newly diagnosed IE." However, some owners of affected dogs report that it appears to cause their dogs to develop mobility problems and pehaps increase liver values.

When combined with phenobarbital (PB), the PB will increase elimination of ZNS, and so the dog may need a higher dose of ZNS to offset this side effect. Dr. Curtis Dewey reports that "There are two reports of liver failure in dogs associated with zonisamide; a subsequent investigation showed that the likelihood of this happening is less than 1%."

Imepitoin

Imepitoin (Pexion, ELB138) is available in the UK and Europe but not in the USA. Imepitoin is a centrally acting antiepileptic substance which inhibits seizures by acting on a specific receptor in the brain cells to reduce the amount of excessive electrical activity present, in order to reduce the number of seizures the dog experiences. In addition, imepitoin has a weak calcium-channel-blocking effect. See this April 2015 report discussing its safety and effectiveness. In the 2015 ACVIM Consensus Statement, the panel gave imepitoin a "High recommendation and likely be effective treatment."

In a February 2017 article, Belgium researchers tested adding phenobarbital or potassium bromide as additional drugs for treatment with imepitoin. These drugs were evaluated in 27 dogs by comparing monthly seizure frequency (MSF), monthly seizure day frequency (MSDF), the presence of cluster seizures during a retrospective 2-month period with a prospective follow-up of 6 months, and the overall responder rate. They concluded that when idiopathic epilepsy is not well controlled with maximum doses of imepitoin alone, either phenobarbital or potassium bromide can be an effective add-on drug which decreases median MSF and MSDF in epileptic dogs unmanageable with a maximum dose of imepitoin. They stated that combination therapy was generally well tolerated and resulted in an improvement in seizure management in the majority of the dogs.

Others

An initial anti-convulsant medication often may be a benzodiazepine (diazepam [Valium], alprazolam, clonazepam, lorazepam), a category of psychoactive drugs which act as tranquilizers by blocking neurotransmitters in the dog’s brain. They are not recommended for dogs with liver or kidney disorders. Side effects in some dogs include diarrhea, vomiting, loss of coordination, and a reduced heart rate.

A July 2006 study of the use of acepromazine maleate (i.e., acetylpromazine), which is a common sedative administered to dogs, involved administering it for tranquilization during hospitalization to 36 dogs with a prior history of seizures and to 11 other dogs to decrease seizure activity. No seizures were observed within 16 hours of its administration in the 36 dogs that received the drug for tranquilization, and seizures abated for from 1.5 to 8 hours or did not recur in 8 of 10 of the 11 dogs that had been actively seizing. Also, excitement-induced seizure frequency was reduced for 2 months in one dog.

• secondary drugs

Secondary drugs are those which may be added to any of the primary drugs if and when the primary drugs do not manage the condition by themselves. In some cases, some clinicians may choose to prescribe a secondary drug as a sole initial treatment.

Levetiracetam

Levetiracetam (Keppra, Elepsia, Spritam) is an anticonvulsant which can also be used in conjunction with phenobarbital and/or potassium bromide. it appears to be relatively safe for dogs, and reportedly rarely has any adverse side effects and does not appear to affect the liver or liver enzymes. In a July 2014 study, researchers found that the adding phenobarbital to a dosage of Levetiracetam significantly altered the disposition of the levetiracetam. See, also, this February 2015 study. The 2015 Consensus Statement rated levetiracetam, "Low recommendation and may not be effective treatment."

In a November 2015 article, six of twelve affected dogs were treated solely with levetiracetam and six were treated solely with phenobarbital. The researchers found that, in the levetiracetam treated dogs, there was no significant difference in the monthly number of seizures before and after treatment, whereas in the phenobarbital treated dogs, there were "significantly fewer seizures after treatment". They concluded that: "In this study levetiracetam was well tolerated but was not effective at the given doses as mono-therapy in dogs with idiopathic epilepsy."

In a May 2007 article, North Carolina State University clinicians reported on a 6-month-old cavalier which had seizures over the period of a year, which were difficult to control with standard anti-convulsants. They diagnosed anorganic aciduria with excessive excretion of hexanoylglycine when the dog was 20 months old. Recurrent and cluster seizures were eventually controlled with the addition of levetiracetam to potassium bromide and phenobarbital.

When combined with phenobarbital (PB), the PB will increase elimination of levetiracetam, and so the dog may need a higher dose of levetiracetam to offset this side effect.

Gabapentin

The anti-convulsant gabapentin (Neurontin, Gabarone) is being prescribed, following an October 2010 study which has shown that between 41% and 55% of dogs have responded to it. Gabapentin works through a receptor on the membranes of brain and peripheral nerve cells. It binds to calcium channels and modulates calcium influx as well as influences GABergic neurotransmission. In humans, gabapentin reportedly does not interact with any other medications, and it is not metabolized, so it is fully excreted in the urine and has no affect upon the liver. However, in dogs, gabapentin is partially metabolized in the liver, and therefore the prescribing neurologist may be expected to order periodic blood tests to check the liver enzymes.

In an October 2018 article, Turkish veterinarians report on the diagnosis and treatment of a 3-year-old neutered female cavalier diagnosed with mitral valve disease which began to experience epileptic seizures. The epilepsy first was treated with levetiracetam, which resulted in the epileptic seizures disappearing. Then, three months later, the cavalier was treated for fleas and ticks with fipronil (Frontline TopSpot, Fiproguard, Flevox, PetArmor). The epileptic attacks "dramatically increased and became more severe just after the fipronil treatment (~7 times per day)." Gabapentin was added to the levetiracetam treatment protocol, and the epileptic seizures. The researchers concluded:

"Fipronil, phenylpyrazole origin and other antiparasitic drugs should be used very carefully and under veterinary consultant supervision due to their side effects especially in epileptic dogs. Finally, gabapentin could be a good option for the alternative add-on therapy to control epileptic seizures in CKCSs."

Oddly, the 2015 ACVIM Consensus Statement does not mention gabapentin.

Pregabalin

A newer anti-convulsant, pregabalin (Lyrica, Accord, Alzain, Lecaent, Milpharm, Prekind, Rewisca, Sandoz, Zentiva), is being prescribed by some neurologists. Dr. Curtis Dewey, board certified veterinary neurologist at Cornell University's college of veterinary medicine, has reported that 78% of dogs responded to pregabalin, and that there was a 57% mean reduction in seizures for the participants who finished the study; all had been diagnosed with difficult-to-control seizures. For more details, see this December 2009 report.

Pregabalin is closely related to gabapentin and was developed by Pfizer, which also developed gabapentin. Pfizer reports that pregabalin is more potent than gabapentin and achieves its effect at lower doses. Doses of pregabalin also reportedly have a longer lasting effect than gabapentin. In a May 2016 study of six brands of pregabalin, the researchers found that "all brands are pharmaceutically equivalent in their quality aspects." They concluded that the lower cost brands of pregabalin could be used to treat epilepsy. The rearchers do not identify the names of the six brands of pregabalin.

Oddly, the 2015 ACVIM Consensus Statement does not mention pregabalin.

Others

Other anti-convulsants, such as topiramate (Topamax), lamotrigine (Lamictal), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), tiagabine (Gabitril), primidone, sodium valproate, and felbamate (felbatol) may be prescribed. Dr. Rusbridge provides a detailed discussion of topiramate on her YouTube channel at this link.

Ketamine (Ketalar) is an intraveous NMDA used as an induction and maintenance agent for sedation and to provide general anesthesia. It is being used more frequently in treatind CM/SM dogs which no longer respond to gabapentin and pregabalin. It blocks sensory perception in humans. It reportedly provides pain relief and controls symptoms of epilspsy.

RETURN TO TOP

• surgery

It is estimated that roughly 30% of dogs diagnosed with epilepsy do not respond to anti-seizure drugs. The alternative option in such cases, other than neurostimulation and/or dietary changes, is a form of surgery called corpus callostomy, described below. Other neurosurgical procedures are performed on humans but not yet on dogs. They are categorized as "resection", "disconnection", and "neurostimulation" surgeries.

corpus callostomy

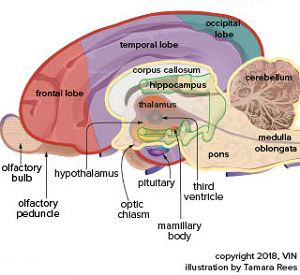

The

corpus callosum is a thick band of nerve fibers (called "commissural

fibers") beneath the cerebral

cortex in the brain, which connects the two hemispheres of the brain and

enables communication between them. It is divided into four parts:

rostrum, genu, body, and splenium.

The

corpus callosum is a thick band of nerve fibers (called "commissural

fibers") beneath the cerebral

cortex in the brain, which connects the two hemispheres of the brain and

enables communication between them. It is divided into four parts:

rostrum, genu, body, and splenium.

A corpus callosotomy (CC) is an intra-cranial surgical procedure to treat epileptic seizures if medications are not successful. It is estimated that roughly 30% of dogs diagnosed with epilepsy do not respond to anti-seizure drugs.

The CC procedure involves cutting all parts or fewer of the band of fibers which make up the corpus callosum. Afterward, the nerves no longer can send seizure signals between the brain’s two hemispheres, making seizures less severe and frequent and may stop them completely. This type of procedure is labeled "disconnection surgery" because it involves a partial severing of a neuronal connection to inhibit the spreading of the seizure activity.

In a November 2021 article, Japanese veterinary neurology specialists performed corpus callosotomies on three cavalier King Charles spaniels diagnosed with drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE). In Case #1, the cavalier required two partial CC surgeries (retaining only the splenium), because the first one ultimately did not reduce the frequency or severity of seizures. Two-plus years after the second surgery, the frequency of seizures was reduced by 93.4%. "The dog’s consciousness and activity improved after both surgeries", and "the patient showed positive behavior, running around and playing with toys with her owners." In Case #2, by a year following a total CC surgery, the seizure rate was reduced by 100%. The cavalier in Case #3 died immediately after partial CC surgery (retaining the genu) of cardiopulmonary arrest, possibly due to mitral valve disease but not confirmed.

multiple subpial transection

Multiple subpial transection (MST) is a disconnection surgery aimed at stopping seizures but preserving areas of the cortex which control functions, such as sensory, language, and motor actions. These also are known as "eloquent" areas of the cortex. In an October 2020 abstract, two laboratory dogs diagnosed with idiopathic epilepsy originating in the frontal lobe. MST surgery was performed in the area where epileptic discharges (ED)were recorded by electrocorticography (ECoG) until the discharges almost disappeared. Both dogs were followed up for seven years and showed no neurological abnormalities following discharge after surgery. ED was observed less frequently and not in the area where MST was performed, for 27 months afterward.

RETURN TO TOP

• natural alternative remedies

In a 2004 article, Dr. H. C. Gurney of Colorado reports success in treating dogs during epileptic seizures by applying ice directly to the dogs' backs at T10 to L4 of the spine. They summarized:.

"Fifty-one epileptic canine patients were successfully treated during an epileptic seizure with a technique involving the application of ice on the back (T10 to L4). This technique was found to be effective in aborting or shortening the duration of ictus. ... Ice is applied as soon as the seizure is observed. Theapplication itself is either a block of ice (i.e., water frozen in a metal ice tray, with the tray applied directly to the seizing patient), or ice (cubes or crushed ice in a plastic bag). The ice is held firmly to the dog’s back, on the area superior to the spinal process from T10 (palpable at the 'low spot' on the canine spine) to L4 (Figure at right). The size of a given ice application is sufficient to cover the described area. Maintain firm pressure in that location until the patient spontaneously recovers sternal recumbency and makes efforts to rise and walk. If the patient is prone to 'chain' episodes or displays evidence of returning to ictus after removal of the ice, the ice should once again be applied until the patient regains sternal recumbence (when chain seizures occur, aggressive medical intervention is necessary). Clients have used bags or boxes of frozen vegetables, but such applications are reported to be less effective. ... The sooner ice was applied during an epileptic event, the more effective the intervention was in stopping or abbreviating the seizure. Also of note was the observation that the canines’ post-ictus recovery time was shorter, and recovery appeared to be augmented."

Holistic veterinarians who practice Traditional Chinese Medicine use acupuncture, Chinese and Western herbal therapy, nutrition, veterinary chiropractic, homeopathy, and homotoxicology as treatment therapies which may be highly beneficial for treating epileptic conditions and other seizures, where a conventional approach either fails to provide relief or produces unacceptable side effects. In a January 2007 article, the researcher reported the success in treating ten affected dogs affected with homeopathic Belladonna therapy.

Traditional Chinese herbal medicines (TCM) and other holistic supplements should be taken only if prescribed by a licensed veterinarian who also is holistically trained in TCM. Search webpages for finding holistic veterinarians in the United States are located here and here.

Cannabinol (CBD

oil) is produced from hemp and marijuana (Cannabis

Sativa) plants. CBD oil mimics the endocannabinoid molecules which the

dog’s (and our) body produces in several different organs. They play

roles in reducing pain, regulating inflammation, and affecting the

immune system, by initially binding to receptors in the brain.

Recommended dosages very widely, from 0.25 mg per kg per day to as much

as 9 mg/kg/day (for epilepsy). However, the maximum recommended dose for

adult humans is only 0.15 mg/kg/daily, the equivalent of 5 drops of 5%

CBD oil.

Cannabinol (CBD

oil) is produced from hemp and marijuana (Cannabis

Sativa) plants. CBD oil mimics the endocannabinoid molecules which the

dog’s (and our) body produces in several different organs. They play

roles in reducing pain, regulating inflammation, and affecting the

immune system, by initially binding to receptors in the brain.

Recommended dosages very widely, from 0.25 mg per kg per day to as much

as 9 mg/kg/day (for epilepsy). However, the maximum recommended dose for

adult humans is only 0.15 mg/kg/daily, the equivalent of 5 drops of 5%

CBD oil.

Varieties of CBD: Cannabidiol-based veterinary products are derived mainly from hemp (Cannabis sativa) and must contain less than 0.3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). This form of CBD can be processed into “full spectrum” or “broad spectrum” and also may be in the form of a “distillate”, in which all THC has been removed, or in the form of CBD “isolate”, which is a purifed powder.

• Full Spectrum: Full spectrum CBD contains other extracts found in the cannabis plant, including terpenes, and up to 0.3% THC.

• Broad Spectrum: Broad spectrum CBD also contains some other cannabis compounds but no more than trace amounts of THC.

• CBD Isolate: CBD isolate is pure CBD and contains no other cannabis plant compounds.

• Naked CBD: Naked CBD describes CBD oil by itself, as opposed to being capsultated or microcapsulated or combined with any other substance, such as deoxycholic acid (DCA).

• Liposomal CBD: This is an orally administered encapsultated CBD which is packaged within liposomes, small fatty cellular sacs which improve bioavailability of the CBD by enabling it to be withstand digesstion in the stomach and degradation in the liver. Lipsomal CBD was tested on dogs in this September 2020 article.

• Cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) is an acid precursor of CBD. It forms CBD when heated. It has been shown in some studies to be more potent that CBD for treating rats. It has been found to be more readily absorbed into the human bloodstream than CBD. Aa theory is that adding CBDA to doses of CBD may make the CBD more absorbable. In this September 2020 article, the investigators found that CBDA is absorbed at least twice as well as CBD in dogs within a 24 hour period, with some differences depending upon the medium used to deliver the oral treatment.

Otherwise untreatable (refractory or intractable) seizures attribured to idiopathic

epilepsy has been the most promising category of disorders responding to

CBD. Again, the numbers of participating dogs have been exceedingly low,

but for the most part, the success rates have been fairly high. In each

of the published studies thus far, the affected dogs continued to be

treated with their previously prescribed antiseizure drugs (ASD).

Otherwise untreatable (refractory or intractable) seizures attribured to idiopathic

epilepsy has been the most promising category of disorders responding to

CBD. Again, the numbers of participating dogs have been exceedingly low,

but for the most part, the success rates have been fairly high. In each

of the published studies thus far, the affected dogs continued to be

treated with their previously prescribed antiseizure drugs (ASD).

As an "add-on" treatment, a very high does of 9 mg/kg of CBD twice a day may have some benefit, but at the risk of impacting the liver.

In a June 2019 article, 9 dogs with intractable idiopathic epilepsy received CBD-infused oil (2.5 mg/kg) twice daily for 12 weeks in addition to their existing antiepileptic treatments. Seven other dogs were in a placebo group. All 9 dogs in the CBD group experienced a reduction in the frequency of seizures, with a 33% median change. However, only 2 dogs were considered responders to the treatment, as defined by reducing seizure frequency by at least 50%. The CBD group dogs also had significant increases in their serum ALP levels by the end of the 12 weeks. The investigators concluded by recommending additional research being necessary to determine the effect of oral CBD treatments on seizure frequency in dogs with epilepsy.

In a July 2022 article, 14 dogs diagnosed with epileptic seizures which were only partially responsive to conventional medications (refractory) were treated orally with a CBD and CBDA-rich hemp product at 2 mg/kg orally every 12 hours for 12 weeks. The dogs also continued to be treated with their prescribed medications. Epileptic seizure frequency decreased. Six of the 14 dogs (43%) experienced a 50% or higher reduction in epileptic activities while being treated with the CBC/CBDA-rich hemp extract. Adverse events included somnolence (drowsiness/strong desire to sleep) and increases in ataxia (loss of coordination). The investigatore concluded that CBD/CBDA-rich hemp extract, in conjunction with other medications, appears safe and can have benefits in reducing the incidence of epileptic seizures.

In a

November 2023 article, two separate and different studies of

treating epiletic dogs with CBD were reported, involving a total of 51

dogs. All of the dogs previously had at least 2 seizures per month while

being treated with at least one antiseizure drug (ASD), most commonly

phenobarbital and/or levetiracetam. The CBD being used was

full-spectrum, containing approximately 100 mg/mL of CBD with trace

amounts of other cannabinoids. The other ingredients were cold-pressed

hemp seed oil and chicken flavoring

The dogs continued to be

administered their prescribed ASDs during these studies.

In the first of these two November 2023 studies, 12 of the dogs were treated with 2.5 mg/kg of CBD oil twice daily for 3 months, without evidence of a treatment effect. In the second study, 39 dogs were treated with 4.5 mg/kg of CBD oil twice daily for 3 months. The overall result of the second study was a 24.1% decrease in seizure activity. The investigators recommended that potential interactions between the CBD and phenobarbital "warranted continued investigation." They concluded that:

"Cannabidol shows promise as an anticonvulsant and warrants further investigation. Care should be taken to monitor liver enzyme activity and bile acid concentrations when this drug is administered chronically to dogs."

See our Cannabis webpage for additional details about CBD, including delivery methods, bioavailability, dosages, and adverse reactions.

RETURN TO TOP

• dietary remedies

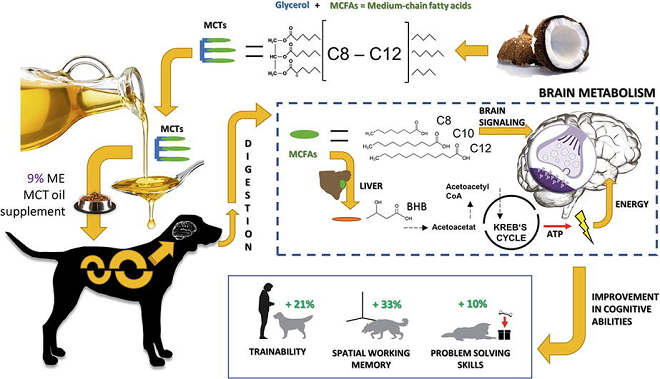

Ketogenic diets*, which include adding medium chain triglycerides (MCTs), which provide the medium chain fatty acids and ketone bodies as auxiliary brain energy, have been shown to be beneficial in treating epiletptic dogs. However, the cavalier King Charles spaniel, as a breed, may be an exception to that general finding that MCTs are beneficial. See this webpage.

* Ketogenic diets are high in fat content (70% to 90% of total calories) and very low in carbohydrates (3% to 5% of total calories).

In a

September 2015 article,

a team of UK researchers fed 21 dogs suspected to have idiopathic epilepsy,

including a cavalier, a dry food kibble

which was either a ketogenic medium-chain TAG (triacylglycerol) diet

(MCTD) or a placebo diet, for three months. Then the dogs were switched

from the one diet to the other for another three months. The results

overall showed that seizure frequencies were "significantly lower when

dogs were fed the MCTD in comparison with the placebo diet. The CKCS's

seizure frequency was reduced from 10 per month on the placebo diet to 5

per month while on the MCTD. The researchers concluded:

In a

September 2015 article,

a team of UK researchers fed 21 dogs suspected to have idiopathic epilepsy,

including a cavalier, a dry food kibble

which was either a ketogenic medium-chain TAG (triacylglycerol) diet

(MCTD) or a placebo diet, for three months. Then the dogs were switched

from the one diet to the other for another three months. The results

overall showed that seizure frequencies were "significantly lower when

dogs were fed the MCTD in comparison with the placebo diet. The CKCS's

seizure frequency was reduced from 10 per month on the placebo diet to 5

per month while on the MCTD. The researchers concluded:

"In conclusion, the data show antiepileptic properties associated with ketogenic diets and provide evidence for the efficacy of the MCTD used in this study as a therapeutic option for epilepsy treatment."

In a February 2016 report, the same team studied 21 dogs affected with idiopathic epilepsy (IE), feeding them a ketogenic MCTD for three months and then a placebo diet for three months. They were looking for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) behaviors in the dogs -- excitability, chasing, and trainability. They found that their "data support the supposition that dogs with IE may exhibit behaviors that resemble ADHD symptoms seen in humans and rodent models of epilepsy and that a MCTD may be able to improve some of these behaviors, along with potentially anxiolytic effects."

In February 2017, Purina announced the launch in the USA of a dry dog food for canine epilepsy patients. The food reportedly is based upon a September 2015 study by veterinary neurologist Dr. Holger Volk. Unfortunately, the ingredients* of this product are a common grain-laden mess of dry food with a few supplements at the end, totally expected from Purina. We cannot imagine how any of these vitamins and other supplements are kept fresh when combined in a bag of triple-cooked kibble. A healthful canned food combining fresh meats and vegetables, topped off with appropriate supplements tailored to the particular disorder and sealed in capsules to maintain freshness, would be much, much better than this joke of a recipe.

*INGREDIENTS: Chicken, chicken meal, corn gluten meal, brewers rice, ground yellow corn, ground wheat, medium-chain triglyceride vegetable oil, corn germ meal, barley, natural flavor, fish oil, dried egg product, L-Arginine, wheat bran, fish meal, mono and dicalcium phosphate, potassium chloride, salt, calcium carbonate, L-Lysine monohydrochloride, Vitamin E supplement, choline chloride, L-ascorbyl-2-polyphosphate (Vitamin C), zinc sulfate, ferrous sulfate, niacin, manganese sulfate, Vitamin A supplement, thiamine mononitrate, soybean oil, calcium pantothenate, Vitamin B-12 supplement, copper sulfate, riboflavin supplement, pyridoxine hydrochloride, garlic oil, folic acid, menadione sodium bisulfite complex (Vitamin K), calcium iodate, biotin, Vitamin D-3 supplement, sodium selenite.

In a November 2020 article, a multi-national team of veterinary reseachers tested the cognitive abilities of 29 dogs diagnosed with epilepsy by including MCT oil as a supplement to the dogs' food over the course of three months. They found from the 18 dogs which completed cognitive testing that consumption of MT oil as 9% of the dogs' total caloric intake that the dogs' spatial-working memory, problem-solving ability, and trainability improved. (See diagram below.) They also report that the MCT oil supplementation increased beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) serum concentration, which correlates with improvement in problem-solving tasks.

Are cavaliers an exception to the rule about MCTs being beneficial? Medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase is an enzyme which is controlled by the ACADM gene. A protein-changing variant of the ACADM gene causes medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase z9 (MCAD) deficiency. MCAD-deficiency is a presumably inherited disorder (an organic aciduria) that prevents the dog's body from converting certain fats to energy, particularly medium-chain fatty acids and particularly during periods without food. Two published studies suggest that MCAD deficiency is fairly common among CKCSs.

In particular, in an October 2022 study of 162 cavaliers, researchers found that 52 of them were carriers of the protein changing variant of ACADM, and another 12 cavaliers were homozygous mutant dogs. That research was prompted by examination of a 3 year old, male neutered cavalier which displayed complex focal seizures and prolonged lethargy. The dog was found to have a single insertion deletion variant of ACADM causing the MCAD deficiency. The affected dog was treated with various dosages of levetiracetam and phenobarbital and was prescribed a low fat diet and a midnight snack consisting of carbohydrates. Prolonged periods of fasting and formulas that contained medium chain triglycerides as primary source of fat were also advised to avoid.

The authors of the November 2020 article advise that MCT-enriched diets may be inappropriate for some CKCSs, based upon the findings of the October 2022 study. They report that they have been testing cavaliers for the ACADM mutation before recommending MCT-enriched diets for those dogs.

RETURN TO TOP

• neurostimulation

Neurostimulation of epileptic dogs involves stimulating the neural tissues to alter their electrical properties and chemical environment and also promoting glial cell activation and proliferation of neuronal progenitor cells. The current methods of neurostimulation of epileptic dogs include vagal (vagus) nerve stimulation (VNS), deep brain stimulation (DBS), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS).

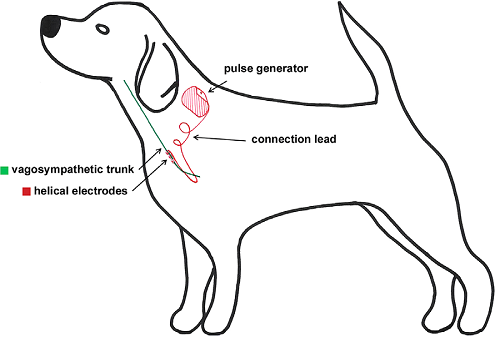

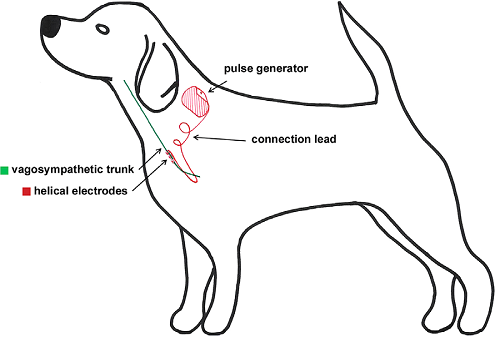

• vagal nerve stimulation (VNS)

The vagus nerve is located next to the trachea. Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) is a procedure which involves implanting an electrical device under the skin, behind the shoulder blade and connected to the vagal nerve. The device sends impulses through the vagus nerve to the brain periodically with the intent of reducing seizures and their severity. In an October 2010 article, Dr. Curtis Dewey reported that vagal stimulators have "failed to demonstrate significant reduction of seizure activity" in dogs.

In

a January 2016

article, Belgium veterinary surgeons reported on the implantation of

VNS devices in a group of ten lab Beagles. They reported that

implantation was "safe and feasible in dogs; however, seroma formation,

twisting of the lead, and dislodgement of the anchor tether were

common." They recommended practical improvements in the technique,

including stable device placement, use of a compression bandage, and

exercise restriction. And they advised that regular evaluation of the

electric lead impedance was important, because altered values can result

in "serious complications".

In

a January 2016

article, Belgium veterinary surgeons reported on the implantation of

VNS devices in a group of ten lab Beagles. They reported that

implantation was "safe and feasible in dogs; however, seroma formation,

twisting of the lead, and dislodgement of the anchor tether were

common." They recommended practical improvements in the technique,

including stable device placement, use of a compression bandage, and

exercise restriction. And they advised that regular evaluation of the

electric lead impedance was important, because altered values can result

in "serious complications".

In a February 2017 article, Dr. Thomas Harcourt-Brown reports some vague success in implanting a VNS device in a UK border collie named Jago. He states:

"Although VNS is rarely curative of epilepsy in humans or dogs, we are very hopeful that that surgery will be effective in helping control Jago’s fits. In recent months his seizures have become so frequent that he has had difficulty in walking and eating. His device will need regular programming over the next few months to get to optimum settings. If it proves effective, it may be possible to reduce the amount of anti-seizure medications he has to take. Its early days yet but this treatment might offer hope for other families with epileptic dogs."

See also the application of vagus nerve stimulation being used experimentally to improve left ventricular dysfunction and slow the progression of heart failure in dogs, on our Mitral Valve Disease page.

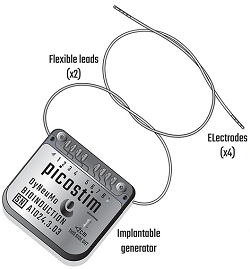

• deep brain stimulation (DBS)

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) involves embedding an electronic

stimulator (right) into the nucleus of the dog's

thalamus,

to select stimulation frequencies which should reinforce normal

physiological behavior and avoid pathological rhythms leading to

seizures. The goal is to reduce and possibly even eliminate epileptic

seizures.

thalamus,

to select stimulation frequencies which should reinforce normal

physiological behavior and avoid pathological rhythms leading to

seizures. The goal is to reduce and possibly even eliminate epileptic

seizures.

In a September 2021 case study article, a 4-year-old Newfoundland/Saint Bernard male with severe drug-resisant idiopathic epilepsy was treated with DBS which was programed with an integrated algorithm that allowed for stimulation to be adjusted to the ultradian, circadian and infradian patterns observed in the patient through slowly-varying adjustments of stimulationand which also enabled adaption of stimulation based on the immediate physiological needs such as a breakthrough seizure or change of posture. Prior to implantation, the dog experiecned cluster seizures which evolved to status epilepticus (SE - continuing attacks of epilepsy without intervals of consciousness, which could lead to brain damage and death) and required emergency treatment. The probes were implanted into the centromedian nucleus of the thalamus. Using combinations of time-based modulation, thalamocortical rhythm-specific tuning of frequency parameters as well as fast-adaptive modes based on activity, the dog experienced no further SE eventsand, no significant cluster seizures.

• transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a non-invasive means of

low-frequency brain stimulation, using

alternating

magnetic fields to create a secondary electric field in the affected

dog, primarily in the cortical areas of the brain. The device is a round

coil whihc rests on the sedated dog's skull. See photo at right.

alternating

magnetic fields to create a secondary electric field in the affected

dog, primarily in the cortical areas of the brain. The device is a round

coil whihc rests on the sedated dog's skull. See photo at right.

In an October 2020 article, seven dogs diagnosed with drug-resistant idopathic epilepsy were sedated and treated with the TMS device for an hour daily for five days. Five other dogs were similarly treated with a sham device. Then in a second phase of the study, the five sham-treated dogs also were treated with the active TMS device. Among the actively treated dogs, seizure frequency reportedly decrased significantly, with the overall effect lasting four months. Howevr, cluster seizures did not change significantly.

RETURN TO TOP

Breeders' Responsibilities

The Canine Inherited Disorders Database recommends that cavaliers which have had seizures should not be bred, nor should their parents and siblings.

RETURN TO TOP

What You Can Do

If your dog has a seizure, take these steps:

• Keep calm. Your dog can sense your emotions, so remain calm and reassuring.

• Keep the dog safe. Clear the area to prevent injury, moving any objects.

• Time the seizure. Write down its duration. If the episode lasts longer than 5 minutes or the dog has multiple seizures in a row, it becomes an emergency, so take the dog to a veterinary clinic immediately.

• Keep track of the symptoms. Write down which behaviors the dog had during the seizure. See the list above for examples.

• Video the seizure, if possible.

• Avoid physical contact with the dog. Do not hold the dog down during a seizure, and avoid contact with or near the dog’s mouth.

• Notify the veterinarian, for advice as to what to do next.

Flea and tick treatments which contain isoxazolines can increase the likelihood that dogs susceptible to seizures will experience them. Isoxazolines lower the threshold of seizures. These flea and tick products include Bravecto, Credelio, Nexgard, Revolution Plus, and Simparica Trio.

The

Canine Epilepsy Project, led by

Dr. Ned Patterson, of the University of

Minnesota's College of Veterinary Medicine, and by Dr. Gary Johnson, of the

University of Missouri's College of Veterinary Medicine, is a collaborative

study into the causes of epilepsy in dogs. Its goal is to find the genes

responsible for epilepsy in dogs so that wise breeding can decrease the

incidence of the disease in dogs, and that, knowing what genes regulate epilepsy

in dogs may help better tailor therapy to the specific cause. Participation by owners of affected dogs and their relatives is essential to the success of this

project. Researchers need DNA samples from dogs who have experienced seizures,

and immediate relatives, both normal and affected. Specifically, they need

samples from all available siblings, parents, and grandparents. If the affected

dog has been bred, all offspring and mates should be sampled as well. Useful

research families are explained in more detail here. Participation in this

research project is confidential - the names of individual owners or dogs will

not be revealed. Data and DNA sample collection instructions and sample

submission forms are available on www.canine-epilepsy.net, or the packet will be

mailed or faxed upon request. Contact Liz Hansen, at the Animal Molecular

Genetics Laboratory, University of Missouri - College of Veterinary Medicine,

email hansenl@missouri.edu Go to the

Canine Epilepsy

Network website for more information.

The

Canine Epilepsy Project, led by

Dr. Ned Patterson, of the University of

Minnesota's College of Veterinary Medicine, and by Dr. Gary Johnson, of the

University of Missouri's College of Veterinary Medicine, is a collaborative

study into the causes of epilepsy in dogs. Its goal is to find the genes

responsible for epilepsy in dogs so that wise breeding can decrease the

incidence of the disease in dogs, and that, knowing what genes regulate epilepsy

in dogs may help better tailor therapy to the specific cause. Participation by owners of affected dogs and their relatives is essential to the success of this

project. Researchers need DNA samples from dogs who have experienced seizures,

and immediate relatives, both normal and affected. Specifically, they need

samples from all available siblings, parents, and grandparents. If the affected

dog has been bred, all offspring and mates should be sampled as well. Useful

research families are explained in more detail here. Participation in this

research project is confidential - the names of individual owners or dogs will

not be revealed. Data and DNA sample collection instructions and sample

submission forms are available on www.canine-epilepsy.net, or the packet will be

mailed or faxed upon request. Contact Liz Hansen, at the Animal Molecular

Genetics Laboratory, University of Missouri - College of Veterinary Medicine,

email hansenl@missouri.edu Go to the

Canine Epilepsy

Network website for more information.

RETURN TO TOP

Research News

November 2023:

Fecal transplants and MCT diet fail to reduce seizures in

cavalier with idiopathic epilepsy.

In a

November 2023 article, veterinary researchers at the University of

Ghent (Fien Verdoodt [right], Myriam Hesta , Tijmen Willemse,

Luc Van Ham, Sofie Bhatti) reported the results of a variety of treatments of a 1.5 year old

female cavalier King Charles spaniel with a history of seizures due to

Tier II idiopathic epilepsy (IE). They started with anti-seizure

medications – first levetiracetam, then phenobarbital, followed by

potassium bromide – without success. Then they switched the cavalier’s

diet to a medium chain triglycerides dog food, Purina Pro Plan

Neurocare, also without a reduction in the frequency of seizures.

Finally, they performed a series of fecal (faecal) microbial transplants

(FMT) over a 10 week period. The FMTs resulted in a “negligible” and

“clinically irrelevant” reduction in seizure frequency. They concluded:

In a

November 2023 article, veterinary researchers at the University of

Ghent (Fien Verdoodt [right], Myriam Hesta , Tijmen Willemse,

Luc Van Ham, Sofie Bhatti) reported the results of a variety of treatments of a 1.5 year old

female cavalier King Charles spaniel with a history of seizures due to

Tier II idiopathic epilepsy (IE). They started with anti-seizure

medications – first levetiracetam, then phenobarbital, followed by

potassium bromide – without success. Then they switched the cavalier’s

diet to a medium chain triglycerides dog food, Purina Pro Plan

Neurocare, also without a reduction in the frequency of seizures.

Finally, they performed a series of fecal (faecal) microbial transplants

(FMT) over a 10 week period. The FMTs resulted in a “negligible” and

“clinically irrelevant” reduction in seizure frequency. They concluded:

“The lack of effect could be due to three main aspects. Firstly, the current protocol might have caused inadequate donor engraftment. 16sDNA sequencing will reveal performance of the protocol. Secondly, variable effects on MSF [mean seizure frequency] might be seen in different dogs, similar to medical and nutritional management of canine IE. Thirdly, the MGBA [microbiota-gut-brain axis] might not be an ideal target in the management of canine IE.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: One possible other cause for the lack of success with

the fecal transplants could be the diet change to a medium chain

triglycerides (MCT) dog food. A significant percentage of CKCSs have

been found to have a medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase z9

deficiency (MCADD) which actually causes seizures as one of its several

nasty side effects. However, the lead investigator, Dr. Verdoodt,

informs us that they did test the cavalier, Pippa, and she was negative

for the mutation. They also switched her daily food to a regular

maintenance diet.

EDITOR’S NOTE: One possible other cause for the lack of success with

the fecal transplants could be the diet change to a medium chain

triglycerides (MCT) dog food. A significant percentage of CKCSs have

been found to have a medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase z9

deficiency (MCADD) which actually causes seizures as one of its several

nasty side effects. However, the lead investigator, Dr. Verdoodt,

informs us that they did test the cavalier, Pippa, and she was negative

for the mutation. They also switched her daily food to a regular

maintenance diet.

July 2023:

Epileptic cavalier resistant to treatment is diagnosed with

malformation of cortical development.

In

a

July 2023 post on Facebook, UK veterinary neurologists Laurent

Garosi (right), Ines Carrera, and Simon Platt reported a case

study of a 2-year-old cavalier King Charles spaniel which has had severe

epileptic seizures since age 4 months. Despite treatment with

anti-seizure medications, the seizures continued to worsen to the point

of 3 to 4 episodes of cluster seizures lasting up to 48 hours. Using MRI

imaging, the clinicians diagnosed malformation of cortical development

(MCDs) based upon observing nodular lesions of neurons which had

migrated into abnormal locations – from adjoining white matter to gray

matter. They suspect the diagnosis is subependymal neuronal heterotopia,

but microscopic tissue study would be required to confirm the diagnosis.

They report that this disorder is very rare in dogs (and humans)

affected with MCDs.

In

a

July 2023 post on Facebook, UK veterinary neurologists Laurent

Garosi (right), Ines Carrera, and Simon Platt reported a case

study of a 2-year-old cavalier King Charles spaniel which has had severe

epileptic seizures since age 4 months. Despite treatment with

anti-seizure medications, the seizures continued to worsen to the point

of 3 to 4 episodes of cluster seizures lasting up to 48 hours. Using MRI

imaging, the clinicians diagnosed malformation of cortical development

(MCDs) based upon observing nodular lesions of neurons which had

migrated into abnormal locations – from adjoining white matter to gray

matter. They suspect the diagnosis is subependymal neuronal heterotopia,

but microscopic tissue study would be required to confirm the diagnosis.

They report that this disorder is very rare in dogs (and humans)

affected with MCDs.

October 2022:

Over 39% of cavaliers have medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A

dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency in a Swiss study.

In

an

October 2022 Swiss study of 162 cavalier King Charles spaniels by

Matthias Christen, Jos Bongers, Déborah Mathis, Vidhya Jagannathan,

Rodrigo Gutierrez Quintana, and Tosso Leeb (right), they found

that 52 of them were carriers of the protein changing variant of the

ACADM gene, and another 12 cavaliers wer homozygous mutant dogs. That

research was prompted by examination of a 3 year old, male neutered

cavalier which displayed complex focal seizures and prolonged lethargy.

The dog was found to have a single insertion deletion variant of ACADM

causing medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency.

The affected dog was treated with various dosages of levetiracetam and

phenobarbital and was prescribed a low fat diet and a midnight snack

consisting of carbohydrates. Prolonged periods of fasting and formulas

that contained medium chain triglycerides as primary source of fat were

also advised to avoid.

In

an

October 2022 Swiss study of 162 cavalier King Charles spaniels by

Matthias Christen, Jos Bongers, Déborah Mathis, Vidhya Jagannathan,

Rodrigo Gutierrez Quintana, and Tosso Leeb (right), they found

that 52 of them were carriers of the protein changing variant of the

ACADM gene, and another 12 cavaliers wer homozygous mutant dogs. That

research was prompted by examination of a 3 year old, male neutered

cavalier which displayed complex focal seizures and prolonged lethargy.

The dog was found to have a single insertion deletion variant of ACADM

causing medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency.

The affected dog was treated with various dosages of levetiracetam and

phenobarbital and was prescribed a low fat diet and a midnight snack

consisting of carbohydrates. Prolonged periods of fasting and formulas

that contained medium chain triglycerides as primary source of fat were

also advised to avoid.

June 2022:

Cavalier with generalized tonic-clonic seizure due to autoimmune

encephalitis is successfully treated with steroids.

In

a June

2022 article, German veterinary clinicians (Enrice I. Huenerfauth

[right], Christian G. Bien, Corinna Bien, Holger A. Volk, Nina

Meyerhoff) report a case of a 1-year-old cavalier King Charles spaniel

which had endured multiple generalized tonic-clonic epileptic seizures,

episodic hyperexcitability alternating with episode of stupor, and

intermittent left circling behavior. The CKCS did not respond to

multiple antiseizure medications (ASMs) -- diazepam followed by

phenobarbital. An autoimmune encephalitis was suspected, and GABAAR

antibodies were detected in his blood serum and cerebral-spinal fluid

(CSF), confirming a diagnosis of anti-GABAA receptor encephalitis. The

cavalier recovered following treatment of immunotherapy with

corticosteroids.

In

a June

2022 article, German veterinary clinicians (Enrice I. Huenerfauth

[right], Christian G. Bien, Corinna Bien, Holger A. Volk, Nina

Meyerhoff) report a case of a 1-year-old cavalier King Charles spaniel

which had endured multiple generalized tonic-clonic epileptic seizures,

episodic hyperexcitability alternating with episode of stupor, and

intermittent left circling behavior. The CKCS did not respond to

multiple antiseizure medications (ASMs) -- diazepam followed by

phenobarbital. An autoimmune encephalitis was suspected, and GABAAR

antibodies were detected in his blood serum and cerebral-spinal fluid

(CSF), confirming a diagnosis of anti-GABAA receptor encephalitis. The

cavalier recovered following treatment of immunotherapy with

corticosteroids.

December 2021:

Cavalier puppy's epileptic-like seizures were caused by a grass

seed lodged near its trigeminal nerve.

In

a

December 2021 article by Andrea De Bonis (right), Oliver

Marsh, and Fabio Stabile, a 4-month-old cavalier with localized seizures

-- head nodding and eyelid twitching -- was suspected of epilepsy.

However, further examination revealed that a grass seed was lodged

within the gums near a molar tooth. Once the seed was surgically

removed, the dog's clinical symptoms disappeared. The clinicians

determined that an inflammatory reaction caused pain (neuralgia) at the

trigeminal nerve, that resulted in the head nodding and twitching. They

recommended that trigeminal neuralgia be considered as a differential

diagnosis of facial seizures before starting any anti-epileptic

treatments.

In

a

December 2021 article by Andrea De Bonis (right), Oliver

Marsh, and Fabio Stabile, a 4-month-old cavalier with localized seizures

-- head nodding and eyelid twitching -- was suspected of epilepsy.

However, further examination revealed that a grass seed was lodged

within the gums near a molar tooth. Once the seed was surgically

removed, the dog's clinical symptoms disappeared. The clinicians

determined that an inflammatory reaction caused pain (neuralgia) at the

trigeminal nerve, that resulted in the head nodding and twitching. They

recommended that trigeminal neuralgia be considered as a differential

diagnosis of facial seizures before starting any anti-epileptic

treatments.

November 2021:

Japanese neurologists perform brain surgery on three cavaliers

with drug-resistant epilepsy.

In

a

November 2021 article, Japanese veterinary neurology specialists

(Rikako Asada, Satoshi Mizuno, Yoshihiko Yu, Yuji Hamamoto, Tetsuya

Anazawa, Daisuke Ito, Masato Kitagawa, Daisuke Hasegawa [right])

performed corpus callosotomies on three cavalier King Charles spaniels

diagnosed with drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE). The corpus callosum is a

thick band of nerve fibers beneath the cerebral cortex in the brain,

which connects the two hemispheres of the brain and enables

communication between them. It is divided into four parts: rostrum,

genu, body, and splenium. A corpus callosotomy (CC) is an intra-cranial

surgical procedure to treat epileptic seizures if medications are not

successful. The procedure involves cutting all parts or fewer of the

band of fibers which make up the corpus callosum. Afterward, the nerves

no longer can send seizure signals between the brain’s two hemispheres,

making seizures less severe and frequent and may stop them completely.

In

a

November 2021 article, Japanese veterinary neurology specialists

(Rikako Asada, Satoshi Mizuno, Yoshihiko Yu, Yuji Hamamoto, Tetsuya

Anazawa, Daisuke Ito, Masato Kitagawa, Daisuke Hasegawa [right])

performed corpus callosotomies on three cavalier King Charles spaniels

diagnosed with drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE). The corpus callosum is a

thick band of nerve fibers beneath the cerebral cortex in the brain,

which connects the two hemispheres of the brain and enables

communication between them. It is divided into four parts: rostrum,

genu, body, and splenium. A corpus callosotomy (CC) is an intra-cranial

surgical procedure to treat epileptic seizures if medications are not

successful. The procedure involves cutting all parts or fewer of the

band of fibers which make up the corpus callosum. Afterward, the nerves

no longer can send seizure signals between the brain’s two hemispheres,

making seizures less severe and frequent and may stop them completely.